Evaluation of Oxidation Process by Ozonation and Glucose Oxidase Enzyme on the Degradation of Benzoquinone in Wheat Flour

Abstract

Background:

Wheat flour is an important food ingredient for humans, which is the basic ingredient of bread and other bakery products.

Objective:

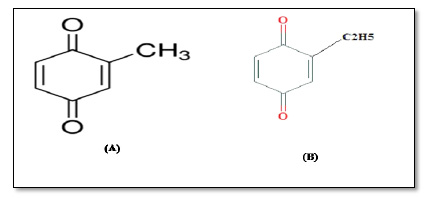

This study aimed to assess the effect of adding Glucose Oxidase (GOX), and exposure to ozone gas on methyl-1, 4-benzoquinone (MBQ), and ethyl-1, 4-benzoquinone (EBQ) secreted by Tribolium castaneum in flour.

Methods:

The flour contaminated by MBQ and EBQ was treated with ozone gas at (10, 20, and 40 ppm) with exposure times (15, 30, and 45 min). Similarly, GOX was added to flour at (10, 15, and 20 ppm), leaving the dough for periods between 10 and 45 min after treatments. The MBQ and EBQ determined by HPLC, and the UV-Visible Spectrophotometer and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) were used to describe the changes that occurred in the main structure of EBQ after ozonation at 40 ppm for 45 min.

Results:

The results indicated that adding GOX enzyme to the flour at level 20 ppm degrade the MBQ to 13.7, 20.23, and 39.6 after 15, 30, and 45 min from mixing time, respectively. On the other hnad, the EBQ degrades to 13.6, 18.9, and 35.9%. In contrast, the percentages of degradation of MBQ and EBQ increases after ozonation at 40 ppm for 45min were 84.1 and 78.8%, respectively. The results obtained by UV–vis spectroscopy and FTIR reflect that many oxidation products formed as aldehydes, ketones, and carboxylic acids.

Conclusion:

In general, ozonation was a reliable treatment for the degradation of benzoquinone in flour.

1. INTRODUCTION

Many insects attack flour during storage, which is frequently under poor storage. Tribolium castaneum (the red flour beetle) is one of the most harmful insects, and it is widespread in mills and stores of cereal products [1, 2]. T. castaneum secretes carcinogenic substances known as BenzoQuinones (BQs) from specialized prothoracic and posts abdominal glands [3, 4]. BQs are the simplest form of quinones, containing two carbonyl groups on a six-membered ring. BQs produced by this insect include two main derivatives, namely methyl-1, 4-Benzoquinone (MBQ), and ethyl-1, 4-Benzoquinone (EBQ) (Fig. 1) [5]. The presence of BQs in wheat grain or flour causes unpleasant odor, and infested flour has a pinkish color, especially with the high concentrations of BQs, which increases with the increase of storage periods and number of insects (T. castaneum) [6-8]. In experimental animals, BQs have a carcinogenic effect, causing tumors in the spleen and liver. Additionally, it suppresses protease enzymes, skin erythema, and tissue necrosis. As well, increasing lipid peroxidation and liver enzymes [9-11]. Consequently, eating products made from contaminated flour by BQs probably causes many problems to human health. Therefore, there is a necessary and urgent need to find an effective and safe method to reduce or remove BQs from contaminated wheat flour. So we believe, using oxidants such as (ozone gas and Glucose oxidase enzyme GOX) could be helpful for this technique. Accordingly, we can use ozone gas as a powerful oxidizing agent that can interact with many chemical groups; moreover, FDA approved ozone gas as a Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) substance. In addition, grain and flour can be treated easily by ozone gas in silos or vessels and stores [12-14]. GOX is known as (EC number 1.1.3.4), which produces hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as a product from glucose oxidation [15, 16], which playing an important role in the interaction with MBQ and EBQ. Consequently, this study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of ozonation at (10, 20, and 40 ppm) with exposure times (15. 30, and 45 min) to degrade MBQ and EBQ formed in flour by T. castaneum. While, the GOX enzyme is added to flour at (10, 15, and 20 ppm) while leaving the dough for 15 to 45 min.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Insect Cultures

Tribolium castaneum was obtained from a stock culture maintained at the stored grain and product pests Department, Plant Protection Research Institute, Agriculture Research Center. It was kept at temperature (28 ±2°C, and 65 ±5% R.H) on wheat flour for two months.

2.2. Chemicals and Solvents

GOX from Aspergillus niger and (MBQ and EBQ) were obtained from Sigma- Aldrich, Lyon, France. All solvents in this study were HPLC-grade. The water was double distilled with a Millipore water purification system (Bedford, MA).

2.3. Infestation of Wheat Flour by T. Castaneum

One kilogram of wheat flour was used and divided into glass jars having the capacity of 100gm. T.castaneum infected these jars with unsexed pairs of insect adults. The jars were left on the bench in the laboratory for three months under laboratory temperature conditions (with an average of 28±2ºC and 65±5%R.H). The previous design was replicated to obtain sufficient quantities of flour to complete the experiment. After three months, the jars containing the flour were sieved thoroughly by 40 wire mesh size to separate the insects. Then the (MBQ, EBQ) were determined in wheat flour before and after treatment by ozone gas and GOX enzyme for each of them.

2.4. Ozonation of Contaminated Samples

The wheat flour was treated with ozone gas using an ozone generator (Model OZO 6 VTTL OZO Max Ltd, Shefford, Quebec Canada; (http://www. ozomax.com). Flour samples (about 250 g) were placed in a cylindrical acrylic container having an inlet valve at one end and an outlet valve at the opposite end. All samples were exposed to ozone gas at (10, 20, and 40 ppm) for 15, 30 and 45 min. Finally, ozone-treated samples were placed in plastic bags, then extraction and determination of MBQ, EBQ were performed by HPLC according to Tomoskozi-Farkas and Daood method [17].

2.5. Adding of GOX Enzyme to Flour

GOX was added to flour at concentrations (10, 15, and 20 ppm), then mixed until the dough was formed, and left for 15, 30, and 45 min before determination of the MBQ and EBQ in samples. The control samples were without the GOX enzyme. The percentages of degradation were calculated from three replicates for each treatment, and the equation used is as follows:

The percentage of degradation BQs =

Where: C is concentrations of MBQ and EBQ in the samples without ozonation or adding GOX.

T is concentrations of MBQ and EBQ in samples after ozonation or adding GOX.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

The general Linear Model procedure of the SPSS ver. 18 (IBM Corp, NY) was used to analyse statistically. The significance of the differences among treatment groups was determined by Waller–Duncan k-ratio. All statements of significance were dependent on the probability of P-value ≤0.05, which was considered to be statistically significant.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Impact of Addition GOX Enzyme on BQs

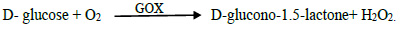

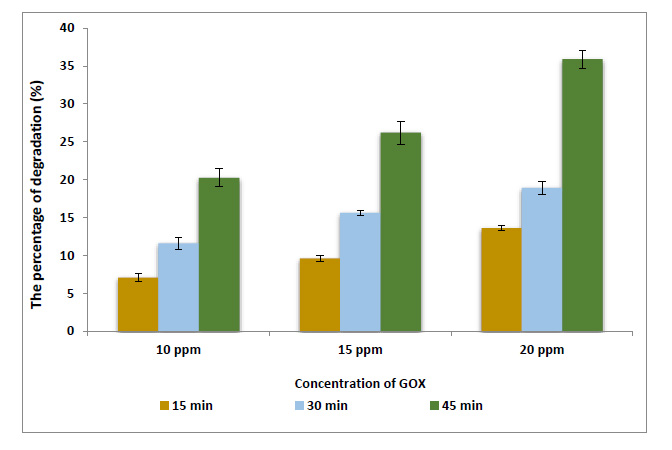

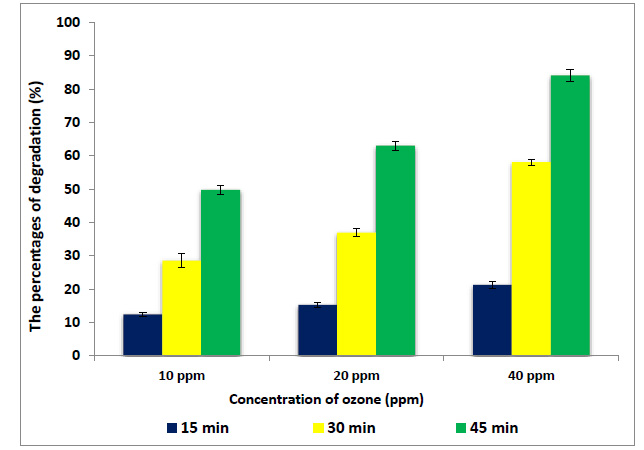

Data presented in Fig. (2) show the percentages of degradation of MBQ after adding GOX at 10 ppm were 9.4, 13.25, and 22.8% after mixing for 15, 30, and 45 min, respectively. The results indicated that the percentages of degradation of MBQ increase to 13.7, 20.23, and 39.6% after mixing for 15, 30, and 45 min, respectively, when the GOX dose increased to 20 ppm. Concerning EBQ, the results in Fig. (3) indicated that the addition of GOX at 20 ppm degraded the EBQ to 13.6, 18.9, and 35.9% after 15, 30, and 45 min from mixing time, respectively. According to previous studies, GOX at these concentrations does not affect the rheological and technological properties of flour and dough; but improves them [18-20]. Hydrogen peroxide is produced from oxidized glucose by glucose oxidase, as Equation 1. H2O2 promotes different reactions in the dough, like disulfide bonding between the water-soluble protein fraction and dityrosine bonding in gluten protein. Accordingly, Hydrogen peroxide reacting with alternating C=C, C=O, and C–C bonds in BQs molecule produces or forms some compounds such as aldehydes. On the other hand, the presence of many minerals and their ions in the chemical composition of flour enhances the work of hydrogen peroxide to decrease the BQs. Furthermore, MBQ is sensitive toward both strong mineral acids and alkali, which cause condensation and decomposition of the compound [21-23]. Finally, the BQs molecule responds to H2O2 through the double bond between C3-C4 in the benzene ring, changing into 2, 3-epoxy-p-benzoquinone. Under conditions of oxidation, 2, 3-epoxy-p-benzoquinone transformed into aldehydes, ketones, acids, and CO2 [24, 25]. On the other hand, the ANOVA analyses of the results Table 1 show that the reduction or degradation of MBQ and EBQ depends significantly on the concentration of the GOX enzyme and the time of mixing (Eq. 1).

|

(1) |

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 19065.84 | 1 | 19065.84 | 7753.661 | 0.000000 |

| BQs | 70.88698 | 1 | 70.88698 | 28.82819 | 0.000000 |

| Con. of GOX | 833.5972 | 2 | 416.7986 | 169.5029 | 0.000000 |

| Time of mix | 3293.995 | 2 | 1646.998 | 669.7981 | 0.000000 |

| BQs* Con. of GOX* Time of mix | 10.35747 | 4 | 2.589369 | 1.05304 | 0.393757 |

| BQs * Time of mix | 20.59651 | 2 | 10.29826 | 4.188077 | 0.023161 |

| Con. of GOX * Time of mix | 201.9491 | 4 | 50.48727 | 20.53207 | 0.000000 |

| BQs * Con. of GOX | 4.220015 | 2 | 2.110007 | 0.858094 | 0.432459 |

| Error | 88.52207 | 36 | 2.458946 | - | - |

| Total | 23589.96 | 54 | - | - | - |

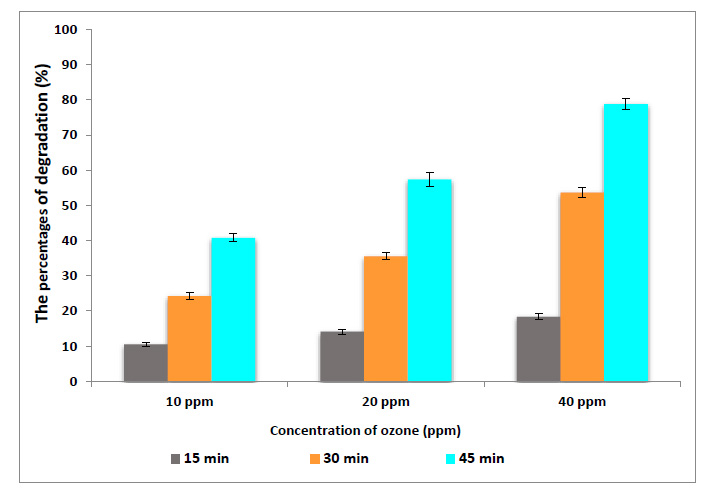

3.2. Ozonolysis Efficiency for BQs in Flour

Data presented in Figs. (4 and 5) show the percentages of degradation of MBQ and EBQ after ozonation at 10, 20 and 40 ppm. The results indicated that the ozonation of wheat flour for 45 min at 10, 20 and 40 ppm degraded the MBQ to 49.8, 63.04, and 84.1%, respectively (Fig. 4). On the other hand, EBQ degraded to 40.8, 57.4, and 78.8% at the same dose and exposure times (Fig. 5). The analysis of ANOVA (Table 2) shows that the doses of ozone gas and exposure time of ozonation have a significant effect on the content of BQs. These results reflect that the ozone gas has shown high efficiency in the degradation of the MBQ and EBQ; this may be due to the high oxidizing power of ozone, which opens the ring and double bonds. The degradation of BQs increases with the excess of the exposure time of ozonation, which may be due to depleted ozone gas with some components of the chemical composition of wheat flour such as protein and carbohydrate, and others. Ozone gas can interact with many compounds and chemical bonds like in the furan ring in aflatoxin, while ozone attacks the double bond at C8–C9. As a result of this reaction, aflatoxin molozonide was formed, which converted to aflatoxin ozonide. This last compound was unstable and changed to aldehydes, ketones, acids, and CO2 [26]. According to this, ozone gas may react with double bonds in BQs, also combine with the C3 in MBQ and EBQ after the peroxo bond breaking [27]. According to many previous studies, treatment of flour by ozone gas at this dose and exposure time has positive effects on rheological and technology properties to obtain improved bakery products [28-30]. The carbonyl group such as aldehydes, ketones, and carboxylic acids were intermediates products for degradation of BQs by ozonation or OH [31].

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 82409.57 | 1 | 82409.57 | 15260.59 | 0.000000 |

| BQs | 225.993 | 1 | 225.993 | 41.84933 | 0.000000 |

| Con. of O3 | 5562.541 | 2 | 2781.271 | 515.0351 | 0.000000 |

| Exposure time | 19892.15 | 2 | 9946.076 | 1841.812 | 0.000000 |

| BQs* Con. of O3* Exposure time | 11.17514 | 4 | 2.793785 | 0.517353 | 0.723438 |

| BQs * Exposure time | 49.84913 | 2 | 24.92456 | 4.615525 | 0.016428 |

| Con. of O3 * Exposure time | 1299.309 | 4 | 324.8272 | 60.15143 | 0.000000 |

| BQs * Con. of O3 | 12.85967 | 2 | 6.429835 | 1.190676 | 0.315704 |

| Error | 194.4057 | 36 | 5.400157 | - | - |

| Total | 109657.9 | 54 | - | - | - |

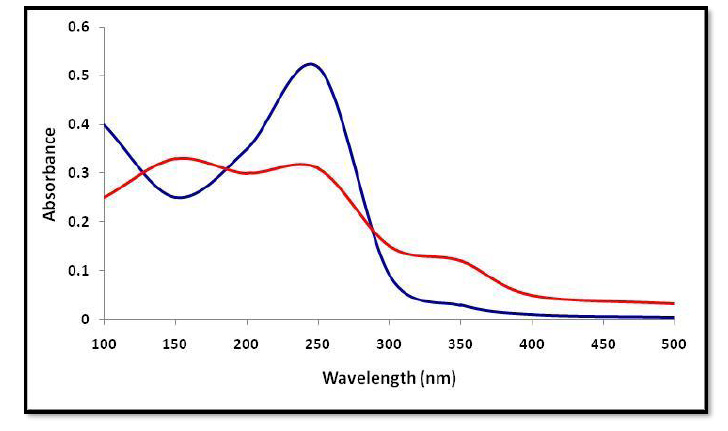

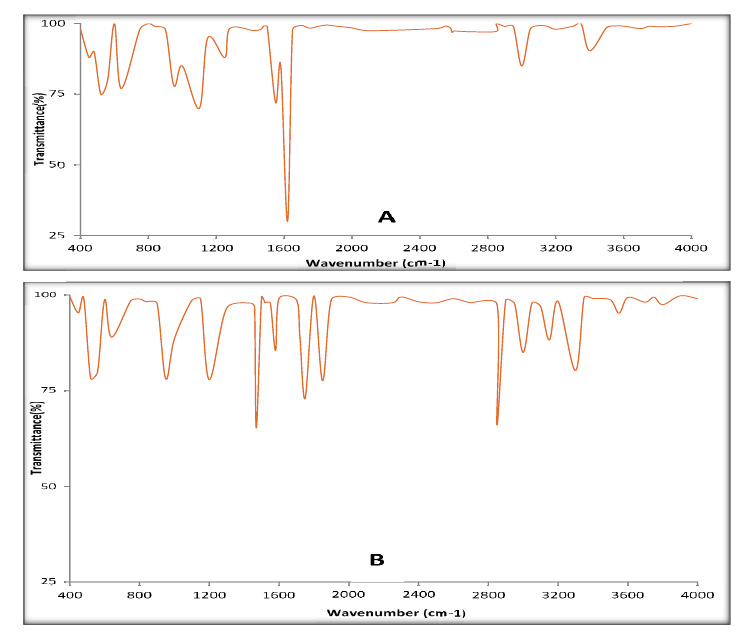

3.3. Characterization of MBQ after Ozonation in vitro

According to obtained results, the best treatment was chosen, which was ozonation of MBQ, as representative for BQs at 40 ppm for 45 min, especially since the difference in structure between methyl and ethyl group only. So, in this study, UV-Visible Spectrophotometer and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) were used to describe the changes that occurred in the structure for BQs. The UV–vis spectroscopy for MBQ untreated showed the absorption peak at 250 nm. The sample revealed many peaks as secondary products after ozonation, as shown in Fig. (6), which may be due to some side reactions, which led to a loss of the basic structure of BQs [32]. FTIR spectrum analysis for MBQ after oxidation by ozone gas indicated the formation of the products of oxidation and the break of the double bond between C=O in C1 and C4, which showed a high absorbance at 1620 cm-1 in the untreated sample. The results of FTIR analysis to the treated sample indicated that many groups appeared like aldehyde at 1750cm-1 and carboxylic at 3550cm-1, etc. (Fig. 7).

CONCLUSION

This study is the first to use Glucose Oxidase (GOX) and ozone gas to degrade MBQ and EBQ secreted by T. castanum in flour. The results concluded that adding GOX enzyme to wheat flour at 20 ppm leads to a decrease of MBQ and EBQ to 39.6 and 35.9%, respectively, after 45min from mixing. The results indicated that the ozonation at 40 ppm for 45 min was more efficient and effective to degrade the MBQ and EBQ to 84.1 and 78.8%, respectively. Finally, ozonation is a promising choice to provide adequate protection for flour during storage.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals/humans were used for studies that are the basis of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All data supporting the findings of this research are available within the article.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.