Gossypol Inhibits Electron Transport and Stimulates ROS Generation in Yarrowia lipolytica Mitochondria

Abstract

This work studied the effect of gossypol on the mitochondrial respiratory chain of Yarrowia lipolytica. The compound was shown to inhibit mitochondrial electron transfer and stimulate generation of reactive oxygen species. The inhibition kinetics in oxidation of various substrates (NADH, succinate, α-glycerophosphate and pyruvate + malate) by isolated mitochondria was investigated. Analysis of the kinetic parameters showed gossypol to inhibit two fragments of the mitochondrial electron transfer chain: a) between coenzyme Q and cytochrome b with KIIIi of 118.3 μM (inhibition by the noncompetitive type), and b) at the level of exogenous NADH dehydrogenase with of KIi 17.2 μM (inhibition by the mixed type).

INTRODUCTION

Gossypol, a triterpenoid aldehyde, is a naturally occurring compound extracted from the cotton plant and other plants of the genus Gossypium infected by phytopathogenic fungi [1]. The compound has been shown to reveal bacteriostatic [2], antifungal [3-5], antitumor [6, 7], antifertility [8, 9] and anti-insect [10] activities. Being biologically active, gossypol has received significant attention as a potential medicinal product and has been extensively studied over the past two decades.

The biological activity of gossypol is mainly due to a disturbance of mitochondrial function, such as modification of the mitochondrial concentration of Ca2+, that associated with membrane fluidity [11], disruption of oxidative phosphorylation by inhibition of mitochondrial succinic dehydrogenase [12], release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol suggesting a mitochondrial-mediated apoptotic mechanism [13, 14]. It is the diversity of mitochondrial dysfunctions that remains the problem of gossypol toxicity opened. The understanding of the mechanism of gossypol action on eukaryotic cells would raise a possibility of clinical implications.

This work studied the effect of gossypol on the mitochondrial respiratory chain of the fungus Yarrowia lipolytica. Kinetic peculiarities of inhibition and hydrogen peroxide formation were examined with regard to the spectrumand mechanism of gossypol action.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The strain Yarrowia lipolytica VKM-Y-2378 was provided by the All-Russian Collection of Microorganisms (Russian Academy of Sciences). Cells were grown at 29°C with constant shaking (200 rpm) in 700-mL flasks containing liquid Reader’s medium (100 mL) supplemented with 0.2% yeast autolysate and Burkholder trace elements. Glucose (1%) was used as a growth substrate.

Mitochondria were isolated from the cells by a previously described enzymatic method [15]. Protein concentration was determined by the biuret reagent.

The rate of oxygen uptake by mitochondria was measured at 21±1°C using the Clark-type platinum electrode in a medium (2 ml) containing 0.6 M mannitol, 20 mM Tris-phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The concentration of oxygen dissolved in the medium was taken to be 250 μM.

Succinate was added at a concentration of 10.0 mM; α-glycerophosphate, at 10.0 mM; NADH, 1.0 mM; and pyruvate + malate (Pyr + Mal), at 5 mM each. Pyr + Mal were added simultaneously for generation of endogenous NADH. Ascorbate and N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (TMPD) (Sigma, USA) were added at 3.0 mM and 0.25 mM, respectively.

All the experiments were carried out in the presence of a classical uncoupler carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) (10 μM, Sigma).

H2O2 production by mitochondria was detected by monitoring 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCDHF-DA) by a spectrofluorimeter (Hitachi MPF-4, Japan). The excitation and emission wavelengths were 480 and 520 nm, respectively [16]. Mitochondria (0.8 mg protein/ml) were incubated in the reaction medium containing 0.6 M mannitol, 20 mM Tris-phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 10 μM CCCP, 20 μM DCDHF-DA and 5 μE horseradish peroxidase. Pyr + Mal were added at a concentration of 5 mM each; succinate, at 10 mM; antimycin A, 5 μM; gossypol, 250 μM.

Gossypol, 2,2′-bi(8-formyl-1,6,7-trihydroxy-5-isopropyl-3-methylnaphthalene) (Sigma), was added to the reaction medium as a methanol solution. The final concentration of methanol was up to 2%. No changes in the rate of oxygen uptake by mitochondria were observed at this methanol concentration. Sensitivity to the inhibitor was expressed as the percentage of inhibition of uncoupled mitochondria before addition of inhibitor, ni = vi/v0·100.

The values of I50 (the dose required to inhibit the enzyme activity by 50%) were estimated by extrapolation from the titration curves.

The root-mean-square deviations at a fivefold determination were: v, ni and I50 = ± 2.5%; Km, V and h = ± 7.5%; Ki= 10%, using the standard program SigmaPlot 10 (USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The mode of gossypol action was investigated using the obligate aerobic fungus Y. lipolytica as a suitable model. This microorganism was taken because its mitochondrial respiratory chain usually has three sites of energy conservation similar to those in plant, fungal or animal cells. However, in contrast with animal mitochondria it contains external NADH : ubiguinone oxidoreductase in addition to complex I, as in plants [17, 18].

We found that endogenous respiration of whole cells noticeably decreases (by 95%) after addition of gossypol (0.25 mM).

A depression of oxygen uptake by gossypol has been shown earlier in respiring yeast and mammalian cells, and antimitochondrial activity is explained by selective inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis [8]. The inhibitory action of gossypol on O2 uptake in human prostate cancer cells has been reported to be due to a disruption of oxidative phosphorylation by inhibition of mitochondrial succinic dehydrogenase [12].

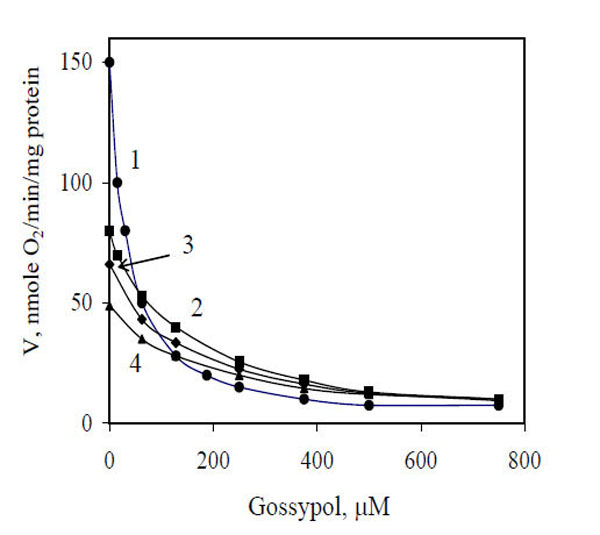

To elucidate the inhibitory action of gossypol on electron transfer, we studied the oxidase activity of mitochondria in the presence of some exogenous substrates, including NADH, succinate, α-glycerophosphate, and piruvate + malate. The results are shown in Fig. (1). The maximum depressing effect of gossypol (95%) was observed during the oxidation of NADH (curve 1), I50 was equal to 30 µM. For other substrates, the calculated I50 values were equivalent and amounted to 190–195 µM.

Influence of gossypol concentrations on mitochondrial respiration in the presence of different exogenous substrates. 1, NADH; 2, α-glycerophosphate; 3, pyruvate + malate; 4, succinate.

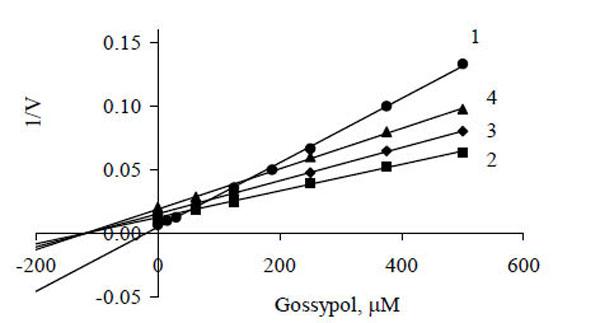

The data of Fig. 1 presented as a Dixon plot yielded a series of straight lines (Fig. 2). Three lines corresponding to three oxidized substrates (succinate, α-glycerophosphate and Pyr + Mal) intersected in one common point (Fig. 2, curves 2–4), that is in accordance with the equality of I50. Most likely, the inhibitor acts at the level of a common electron carrier in the respiratory chain, e.g., between ubiquinone and cytochrome oxidase, and its inhibitory action is independent of the type of oxidized substrate. These lines can be imagined to correspond to one substrate at different concentrations, i.e., electrons transferred from respective dehydrogenases to the respiratory chain (in accordance with the rates of oxygen uptake by mitochondria without any inhibitor) (Fig. 1).

Dixon plots of gossypol inhibition of oxygen consumption by mitochondria during oxidation of NADH (1), α-glycerophosphate (2), pyruvate + malate (3) and succinate (4). Experimental values are taken from Fig. (1).

It should be noted that the concentration of transferred electrons could not be expressed explicitly; and the equality of I50 for three oxidized substrates (Fig. 1, curves 2–4) is approximate. Despite these weak points we think that the use of the Dixon plot to determine the inhibition parameters (Fig. 2) is admissible.

Intersection of three lines on the abscissa (Fig. 2) and approximation of the data shows that inhibition of electron transfer by gossypol can be assigned to either the catalytic (IIIi) type according to the parametric classification [19, 20] or to the noncompetitive type in compliance with the traditional classification [20]. The kinetic parameters were determined to be

with KIIIi of 118.3 μM irrespective of substrate oxidized.

Our further investigation showed that oxidation of ascorbate as the respiratory substrate in the presence of TMPD was insensitive to gossypol but was inhibited by cyanide (95%). From these results the gossypol coupling site is between coenzyme Q and cytochrome b.

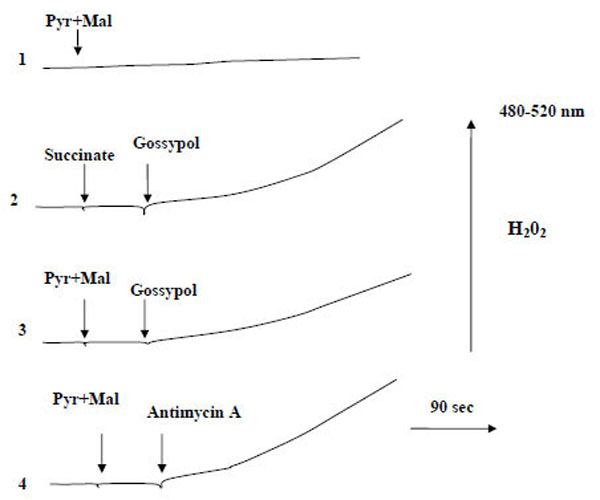

These findings suggest that reactive oxygen species (ROS), namely hydrogen peroxide, are produced. Fig. (3) shows representative traces of H2O2 production by mitochondria oxidizing succinate or pyruvate + malate. Addition of gossypol significantly increased the rate of H2O2 production (curves 2, 3). Antimycin A (a classical inhibitor of electron transfer at the level of cytochrome b) also increased the H2O2 production rate (curve 4). These results show that gossypol stimulates ROS production implying the ubiquinone pool in H2O2 generation.

Influence of gossypol on H2O2 generation by mitochondria. Mitochondria (0.8 mg protein/ml) were incubated in a reaction medium containing 0.6 M mannitol, 20 mM Tris-phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), 10 μM CCCP, 20 μM DCDHF-DA and 5 U horseradish peroxidase. Pyruvate and malate were added at a concentration of 5 mM each; succinate, 10 mM; antimycin A, 5 µM; gossypol, 250 µM.

On the other hand, gossypol, as shown earlier [13], does not increase the level of ROS and antioxidants and induces apoptosis in HL-60 cells through a ROS-independent mitochondrial dysfunction pathway. It has also been shown that gossypol activates genes responsible for the biosynthesis of antioxidant enzymes [6].

As can be seen from Fig. (2), the dependence of 1/v versus gossypol concentration for exogenous NADH oxidation (curve 1) contrasted with that for the oxidation of the other substrates (curves 2-4), which suggests another peculiarity of inhibition. Obviously, there was the second site of gossypol binding the mitochondrial membrane, at the level of external NADH-dehydrogenase.

It has been shown earlier [21,22] that nucleotide-metabolizing enzymes are major targets for the action of gossypol in mammalian cells. Apparently, what we have here is the direct interaction of gossypol with the nucleotide-binding site of the enzyme, which provides a possible mechanism for the disturbance of normal cell function, namely, the disturbance of the balance between NADH and NAD+ (NAD+ recycle) in the cytosol.

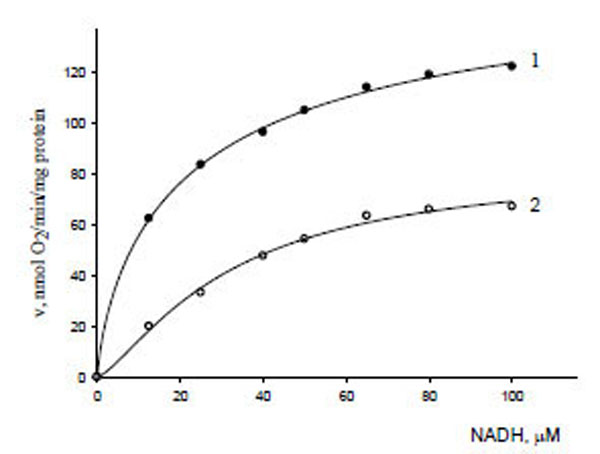

The influence of gossypol on NADH oxidation (oxygen uptake) was tested to characterize the strength of gossypol–external NADH dehydrogenase binding. The dependence of the initial rates of NADH oxidation by isolated mitochondria on NADH concentration in the absence (curve 1) and presence (curve 2) of gossypol (30 μM) is given in Fig. (4). These curves were subjected to nonlinear extrapolation using a three-parameter Hill equation as described earlier [23]:

Dependence of the initial reaction rates of oxygen uptake by mitochondria on NADH concentration in the absence (1) and presence (2) of gossypol (30 µM).

The kinetic parameters of NADH oxidation were V0 = 183.2 μmol/min μg protein, = 13.91 μM, (h0 = 1.25) in the absence of gossypol (curve 1), and V' = 84.06 μmol/min μg protein, = 31.82 μM, (h' = 1.33) in the presence of gossypol (curve 2).

Based on the parametric classification of enzyme reaction types, the above data satisfied every attribute of biparametrically coordinated, Ii (or mixed) type inhibition [21]:

From these results, the enzyme exhibited a weak positive cooperativity by NADH and, moreover, the variation interval of the Hill coefficient (± 6.5%) is within the framework of the calculation error. That allowed us to estimate the enzyme inhibition constant for gossypol (KIi), i.e., to determine the affinity of the inhibitor to the enzyme, using a modified equation [19]:

The data obtained demonstrate that gossypol has an affinity to the enzyme as the substrate oxidized does which makes enzyme-substrate binding difficult ( ) and reduces the maximal reaction rate . The inhibition constant value calculated (KIi) is almost seven times lower than that for the other oxidized substrates (KIIIi).

CONCLUSION

In this work, we showed that gossypol inhibited the electron transfer in fungal mitochondria, which led to a disturbance of energy metabolism. The proposed kinetic approach enabled us to determine that gossypol inhibited two fragments of the mitochondrial electron transfer chain with different intensity: between coenzyme Q and cytochrome b, with KIIIi equal to 118.3 μM; and at the level of exogenous NADH dehydrogenase, with KIi equal to 17.2 μM. We also showed that inhibition of yeast cell respiration led to increase the concentration of ROS toxic for the cells.

The toxic effect of gossypol has been earlier observed in fungi: gossypol inhibited the growth of plant pathogens Fusarium decemcellulare [3], F. oxysporum [4] and Rhizoctonia solani [5]. From our results, the toxicity of gossypol for fungi can be also explained by the antimitochondrial effect: inhibition of cell respiration as well as stimulation of ROS generation.

As mentioned above, there are many modes of gossypol action in mitochondria; it is true, though, that this effect has been studied mainly in mammalian cells. It is the antimitochondrial properties of gossypol that can be the basis of its use as promising therapeutics (as an antifertility, anticancer, antiviral and/or antipathogenic agent) with great potential in clinical practice.

These data is a supplement to а variety of mechanisms of gossypol action in mitochondria and can be of interest for the debate on the interrelations between phytopathogens, plants and animals including humans.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link] [PMC Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PMC Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]