All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Predominantly Cytoplasmic Localization in Yeast of ASR1, a Non-Receptor Transcription Factor from Plants

Abstract

The Asr gene family (named after abscisic acid, stress and ripening), currently classified as a novel group of the LEA superfamily, is exclusively present in the genomes of seed plants, except for the Brassicaceae family. It is associated with water-deficit stress and is involved in adaptation to dry climates. Motivated by separate reports depicting ASR proteins as either transcription factors or chaperones, we decided to determine the intracellular localization of ASR proteins. For that purpose, we employed an in vivo eukaryotic expression system, the heterologous model Saccharomyces cerevisiae, including wild type strains as well as mutants in which the variant ASR1 previously proved to be functionally protective against osmotic stress. Our methodology involved immunofluorescence-based confocal microscopy, without artificially altering the native structure of the protein under study. Results show that, in both normal and osmotic stress conditions, recombinant ASR1 turned out to localize mainly to the cytoplasm, irrespective of the genotype used, revealing a scattered distribution in the form of dots or granules. The results are discussed in terms of a plausible dual (cytoplasmic and nuclear) role of ASR proteins.

INTRODUCTION

In part because drought is currently a major agronomic problem [1], molecular responses to water loss have been extensively studied using a variety of biological models, such as dried bacteria, yeast, plants living in deserts and anhydrobiotic plants and invertebrate animals [2-8].

Among the many different proteins that accumulate in both mild and severe dehydration, the most extensively characterized are those belonging to the LEA superfamily, which are classified into several groups based on particular amino acid sequence motifs [9]. There are more than fifty LEA-encoding genes in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome, most of which have abscisic acid response elements (ABRE) in their transcriptional enhancers [10].

Similarly, the smaller Asr gene family (named after abscisic acid, stress and ripening) is associated with water-deficit stress too and is involved in adaptation to dry climates [4]. Its history apparently extends back to gymnosperms [11], the first seed plants, appearing during the late Carboniferous period, at least 300 million years ago. In this scenario, drought-resistant features of conifers like pine might have been critical during their evolution during the Permian, when the continental Earth turned cold and dry. For convenience, the encoded proteins (ASRs) have recently been classified as a new group of LEAs because of the sharing of some common properties such as a small size, hydrophilicity and expression patterns [12, 13].

Attempts towards the identification of the precise biochemical function of ASR proteins seem contradictory. On one hand, it has been claimed that tomato ASR1 binds to a very short DNA consensus sequence [14], which is in agreement with the direct microscopic visualization of ASR1 bound to DNA with high affinity [15] and the need of a nuclear localization signal (NLS) for nuclear export [16]. In addition, one-hybrid assays in yeast allowed ASR proteins to be regarded as transcription factors targeting the enhancer of a sugar transporter gene [17]. On the other hand, there is evidence that they also localize to the cytosol. The reports supporting the latter alternative are based on i) subcellular fractionation experiments, with the associated risk of fraction cross-contamination [14], ii) in vivo expression of ASR (14 kDa) fused to GFP (27 kDa) in recombinant virus-inoculated plant leaves followed by microscopic visualization [16], with the concomitant drawback that the long fluorescent moiety might alter the natural intracellular trafficking of the protein under study.

Therefore, to determine more accurately the intracellular localization of ASR proteins without altering their native structure, we employed an in vivo methodology in the heterologous model eukaryotic system Saccharomyces cerevisiae, in which the variant ASR1 has already proved to be functionally protective against the lethality caused by osmotic stress [18].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast Strains and Growth Conditions

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study are the wild type YPH102 (MATa ura3-52 lys2-801amber ade2-101ochre his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1) and the isogenic mutant JBY13 (YPH499 (MATa ura3-52 lys2-801amber ade2-101ochre trp1-Δ63 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1) + hog1Δ::TRP1). Yeast was grown at 30°C in YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone and 2% glucose) or in synthetic complete (SC) medium (0.17% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and ammonium sulfate supplemented with Ura-Dropout and 10 mM ammonium sulfate). Carbon sources for synthetic medium were 2% raffinose, 2% glucose or 1% galactose.

Stress Assays

Cells from raffinose SC medium were inoculated in galactose SC medium and incubated for 20 minutes at 30ºC. Cells were then transferred either to glucose SC medium or to glucose SC medium containing 0.5 M NaCl. Samples were withdrawn after 10 and 20 minutes.

Plasmids and Yeast Transformation

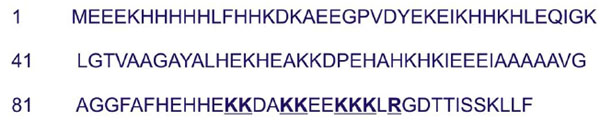

The Lycoperson esculentumAsr1 full-length cDNA, containing the NLS (amino acid positions 92-105) (Fig. 1), was subcloned into the Xba1/Kpn1 site of the high-copy-number shuttle vector pYES2 (Invitrogen, CH Groningen, The Netherlands) that contains the GAL1 promoter [18]. Wild type and mutant cells were transformed with the recombinant vector (pYES2-Asr1) using the method described by Chen et al. (1992)[19]. As a control, the same strains were transformed with the empty vector.

Amino acid sequence of ASR1, the ASR variant chosen for this study. Highlighted are key residues within the NLS (positions 92-105) [16].

Indirect Immunofluorescence

ASR1 was visualized by indirect immunofluorescence on whole fixed cells. Cells were fixed by the addition of 1/10 volume of 37 % formaldehyde and incubated at 37ºC for 5 minutes and then at room temperature for 1 hour. Washed cells were resuspended in sorbitol buffer (1.2 M sorbitol and 100 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.4). Cell walls were digested incubating with 80 units of cytohelycase (β-(1,3)D-glucanase, IBF biotechnics) at 30ºC for 90 minutes. Cells were permeabilized incubating with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 4 minutes, washed and then resuspended in 1% bovine serum albumin. After 20 minutes, cells were centrifuged and resuspended in rabbit ASR1-specific antiserum or preimmune serum (Bio-Synthesis Incorporated) at a working dilution of 1:50 and 1 mg/ml ribonuclease A (Sigma). The secondary antibody was FITC goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulins G (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a dilution of 1:100. DNA was stained with 50 µg/ml propidium iodide. Cells were imaged (1500X) using a confocal microscope (Fluoview FV300 BS61, Olympus, Melville, NY).

Control cells transformed with the empty plasmid pYES2 showed no green fluorescence.

RESULTS

In order to determine the intracellular localization of tomato ASR proteins, we chose ASR1, the member of the family most extensively studied from a structural viewpoint. Therefore, both wild type and hog1Δ yeast cells were transformed with pYES2-Asr1.

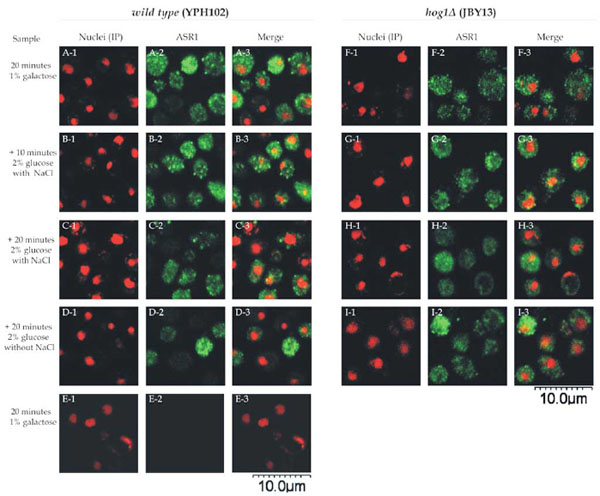

In normal, non-stressed conditions, ASR1 localized mainly to the cytoplasm (Fig. 2, panels A and E). When cells were subjected to osmotic stress (0.5 M NaCl), ASR1 remained cytoplasmic at least up to 20 minutes (Fig. 2, panels B. C, F and G).

Intracellular localization of ASR1 in yeast cells. Wild type cells (YPH102 strain) (panels A1-E3) and hog1Δ (JBY13 strain) (F1-I3 panels) transformed with pYES2-Asr1 were incubated in 1% galactose SC medium. After 20 minutes, samples were withdrawn (panels A, E and F) and remaining cells were transferred to 2% glucose fresh SC medium with (panels B, C, G and H) or without (panels D and I) 0.5 M NaCl. Samples were withdrawn at 10 minutes (panels B and G) or 20 minutes (panels C, D, H and I). Nuclei were stained with propidium iodide (panels 1). Cells were processed for indirect immunofluorescence with ASR1-specific antiserum (panels 2), except for panels E where a pre-immune serum was used. Merged images are shown in panels 3.

Green fluorescence was not observed when a preimmune serum , instead of an ASR1-specific antiserum, was used.

A detailed observation of the images reveals that ASR1 dissemination within the cytoplasm is not homogeneous, but rather scattered in the form of dots or granules. These aggregates seemed to fade at longer incubation times irrespective of the presence of NaCl (Fig. 2 panels C, D, G and H). The same intracellular localization of ASR1 was observed in both strains analysed, indicating that even under the conditions in which ASR1 is functional against osmotic stress (namely the hog1Δ strain treated with salt), this protein does not translocate to the nucleus.

DISCUSSION

The conclusion drawn from this work is that ASR1 is mainly cytoplasmic, contrasting with the notion that it acts as a transcription factor [17] and with theoretical computational results from the web-server Cell-Ploc (http://chou.med. harvard.edu/bioinf/Cell-PLoc/) [20, 21]. The latter is a powerful subcellular location predictor, which yields a nuclear localization for ASR1 when comparing it with a plant database. However, a non-nuclear localization is predicted when using a larger eukaryotic database created by inputting experimentally validated proteins. The discrepancy may be owing to intra- or intermolecular masking of NLSs in many non-plant proteins under nuclear import regulation [22].

The observed cytoplasmic localization is a long-recognized feature of steroid hormone-receptor transcription factors [23] but is quite intriguing for non-receptor ones like ASR proteins. The observed cytoplasmic nature of ASR1 here reported is consistent with recent evidence showing ASR1 as a chaperone [24]. Whether the observed scattered distribution in the cytoplasm is due to artificial overexpression in yeast or to association to intracellular structures such as organelles or stress granules [25, 26] remains to be further investigated.

Modern proteomics studies have confirmed over-representation of both classic LEAs and ASRs upon dehydration [27], thus suggesting that these molecules actively participate in the cellular response mounted to cope with this type of stress. In this respect, several biochemical roles have been proposed for the widespread, heterogeneous and expanding LEA protein family, whose members are known to be natively unfolded and fold as a consequence of water-deficit stress [9]. For example, certain purified LEA proteins have been reported to act as chaperones, protecting liposome integrity or enzyme activity upon drying [28]. Mechanistically, LEAs seem to protect other proteins –keeping them from aggregating- or membranes in a fashion similar to sugars [29], perhaps by acting as water replacement molecules [6]. At very low water content and high cytoplasmic viscosity, these proteins may also confer stability to the cytoplasmic glassy matrix formed upon extreme drying conditions, as suggested by studies of dried carrot somatic embryos [30]. Such activity is likely to occur via an increased glass transition temperature (Tg) of sugars. In this scenario, LEAs and sugars have been proposed to form a tight hydrogen bonding network together in the dehydrated cytoplasm [31].

The methodology used by us in this work avoided the need of fusing ASR1 to a long amino acid fluorescent tract as a reporter for tracing protein localization. In this context, the danger of formation of fluorescent particles has been wisely warned by Lenassi-Zupan et al. (2004) [32] when using GFP in fusion with other proteins in high-level expression systems, which could lead to wrong interpretations of targeting. Another similar risk is the eventual masking of NLSs in GFP-fused proteins [33]. Our immunofluorescence-based detection system coupled to microscopic visualization of in vivo-expressed unmodified ASR1 circumvents these drawbacks, thus reinforcing the interesting notion of a plausible dual role (i.e. both transcription factor and chaperone) for ASR proteins, initially recognized as solely nuclear.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by University of Buenos Aires (UBA), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas (CONICET), Argentina and Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (ANPCyT), Argentina. The authors thank Mr. Atilano Roberto Fernández (CONICET) for his valuable assistance with the confocal microscopy experiments.

REFERENCES

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link] [PMC Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link] [PMC Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link] [PMC Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link] [PMC Link]

[PubMed Link] [PMC Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link] [PMC Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]