All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Alzheimer’s Biochemistry and Therapeutic Prospects of Functional Foods-based Strategies

Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD)is a complex and multifactorial neurodegenerative disorder characterized by common pathogenic features, such as the development of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and the formation of neurofibrillary tangles from hyperphosphorylated tau proteins. Although the cholinergic hypothesis, which focuses on the cognitive role of acetylcholine, remains a fundamental concept, recent studies have reported that neuroinflammation and oxidative stress play pivotal roles in the pathology of AD. Besides these pathways, aging, diverse diseases, environmental factors, and genetic conditions are well-known risk factors for AD. Currently, no disease-modifying treatment exists for AD. The available therapies provide only symptomatic relief and are often associated with adverse side effects. Meanwhile, growing evidence suggests that dietary interventions rich in anti-inflammatory and antioxidant compounds can modulate inflammatory cytokines and neutralize free radicals, thereby offering a promising approach to mitigate AD risk and potentially delay its onset. Future research should focus on developing novel therapeutic strategies that specifically target the restoration of the oxidative–inflammatory balance, moving beyond symptomatic relief to address the key pathological pathways in AD.

1. INTRODUCTION

Neurodegenerative diseases are a group of disorders characterized by the progressive loss of neuronal structure or function, which eventually leads to the death of the affected neurons [1]. Among them, Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common and accounts for the majority of dementia cases worldwide [2, 3]. Clinically, AD manifests as progressive memory loss, cognitive decline, and difficulty carrying out everyday tasks, all of which harm the quality of life for those affected [3]. As the illness progresses, people frequently need full-time care, which places a tremendous social and financial strain on families and healthcare systems around the globe. Because of this, AD is not only a significant contributor to morbidity but also a major cause of the global health crisis related to aging populations [4].

From a histological standpoint, AD development is associated with three main neuropathological traits: the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), synaptic degeneration, and the buildup of extracellular amyloid plaques, which occurs in the neocortex, hippocampal regions, and other subcortical regions essential to cognitive function [5]. People over 65 are typically affected, and early onset before age 65 is uncommon [6]. The global aging population is experiencing an alarming rise in the prevalence of AD. The World Alzheimer's Report states that 46.8 million individuals globally are estimated to be affected by AD, and this number is expected to triple by 2050 as the population ages, particularly if interventions are ineffective [7, 8]. Additionally, it has been found that approximately 60–80% of the incidence of AD can be attributed to heritable traits. Of these, there are currently over 40 genetically susceptible loci linked to AD, the strongest of which is the apolipoprotein E (APOE) allele [8].

Although metabolic byproducts are required for physiological function, reactive oxygen species (ROS) can be harmful in excess. ROS can promote oxidative stress, harming every part of the body, especially the central nervous system, and compromising mitochondrial function [9]. An increasing amount of research points to the role of oxidative stress in AD development by facilitating the deposition of Aβ, tau hyperphosphorylation, and the subsequent loss of neurons and synapses [10]. Concurrently, persistent neuroinflammation, which is defined by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the activation of microglia, worsens neuronal damage and advances the course of the disease [11]. Recent data indicate that inflammation and oxidative stress work together to create a vicious cycle that exacerbates AD neurodegeneration [12].

Despite decades of research, there is still no cure for AD [13]. Current therapies, like N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, only provide modest symptom reduction and frequently have serious adverse effects [3, 14]. In the meantime, attempts to directly target tau pathology and Aβ have not yet shown significant progress in clinical trials [15]. Consequently, there is increasing interest in investigating complementary or alternative approaches that can modulate the biochemical mechanisms underlying AD. In recent years, natural bioactive substances with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, such as quercetin, carotenoids, kaempferol, resveratrol, and curcumin, have gained attention. These substances have the potential to act at several stages of the disease cascade by lowering oxidative damage, managing neuroinflammation, and maintaining neuronal function, in contrast to single-target pharmacological agents [16-18].

Although oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in AD have been covered in great detail in earlier reviews, these mechanisms are frequently addressed independently or primarily focus on synthetic pharmacological interventions. Furthermore, despite the growing awareness of the oxido-inflammatory balance, there is still a lack of comprehensive research on how functional foods can concurrently alter oxidative and inflammatory pathways, providing a multitarget and safer substitute. With a focus on functional food-based interventions that target the oxidative-inflammatory balance as a promising avenue for managing AD, this review highlights the biochemical mechanisms by which functional foods exert neuroprotective effects in AD, while also summarizing the key preclinical findings and existing clinical trial results to provide an integrative synopsis of their translational potential.

2. METHODS

This review included a search for relevant articles from online databases (Google Scholar, PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus, and Web of Science). Articles published until 2025 were considered. Articles published in the English language between 2010 and 2025 were identified and extracted using the search terms “biochemistry of Alzheimer’s”, “Alzheimer's and amyloid beta”, “tau protein and AD”, “cholinergic hypothesis”, “oxidative damage and inflammation in AD”, “risk factors in AD”, and “therapeutic strategies in AD”. The inclusion criteria were relevance to AD biochemistry, peer-reviewed articles (original research, systematic reviews, or meta-analyses), and availability of full text. Articles were excluded if they lacked full-text access, were not directly related to the biochemistry of AD, were published outside the specified timeframe, or lacked scientific rigor. A total of 287 articles were initially retrieved, with 77 excluded, resulting in the final set used in this review.

3. AD NEUROPATHOLOGY

3.1. Amyloid-β (Aβ) Peptide

The Aβ peptide consists of 42 amino acids and originates from the amyloid-β precursor protein (APP). On chromosome 21, there is a gene encoding APP [14]. β-, γ-, and α-secretases break down APP at different domains. β-Secretase cleaves APP first, and γ-secretase cleaves it again, producing Aβ peptides of varying lengths, such as Aβ40 and Aβ42, which differ in the number of residues; Aβ42 has two additional residues at its C-terminus compared to Aβ40. Most Aβ plaques in AD are formed by the Aβ42 isoform, although some plaques exclusively contain this isoform [19].

The normal function of APP involves regulating synaptic plasticity, cell signaling, and neuronal growth. It is also linked to the restoration of damaged neurons, particularly under stress or injury conditions [20]. AD is primarily caused by the pathological cleavage of APP by β- and γ-secretases, which results in the formation of Aβ peptides [19]. One could argue that the main problem in AD pathogenesis may be the disruption of APP’s normal physiological roles, rather than only the accumulation of its breakdown products (Aβ plaques), even though Aβ aggregation is a hallmark of AD. This is because the physiological functions of APP are critical for maintaining neuronal health and functionality [21]. These functions may be compromised long before Aβ plaques accumulate to pathological levels due to dysregulated APP processing or APP gene mutations [22]. Additionally, the buildup of Aβ plaques may not be the sole cause of neurodegeneration but rather a consequence of a fundamental impairment in APP function [23].

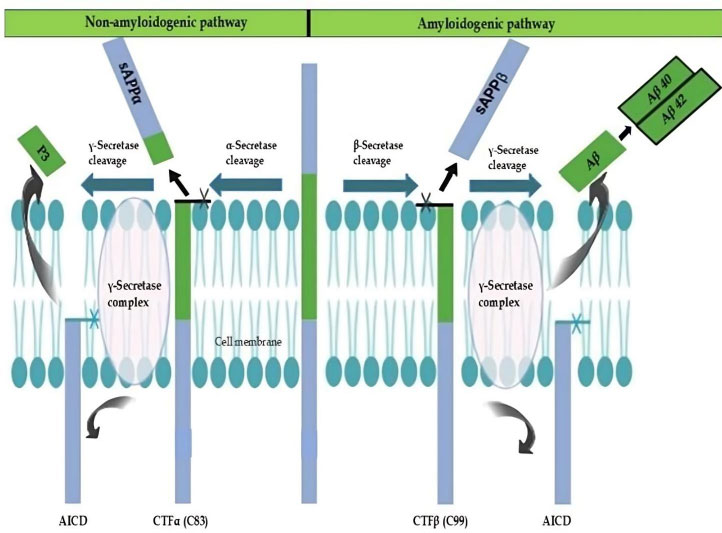

In healthy neurons, α- and γ-secretase enzymes process APP along the non-amyloidogenic pathway (Fig. 1) [24]. This reaction produces soluble polypeptides that can later be recycled and degraded in the cell. β- and γ-secretases can also process APP through the amyloidogenic pathway, as shown in Fig. (1), generating an insoluble peptide known as Aβ. Aβ peptides aggregate to form plaques that are detrimental to neuronal cells. At least three major cellular problems may arise when Aβ plaques accumulate. Aβ plaques may disrupt communication between healthy neurons, and when neuronal signaling is impaired, the brain suffers damage and loses specific functions [25]. The brain contains two major Aβ species—Aβ42 and Aβ40. Although Aβ40 is more abundant in soluble form, Aβ42 is the primary component of Aβ plaques [26].

The brain’s primary β-secretase is BACE1 (β-Site APP-Cleaving Enzyme 1). Neurotoxic forms of Aβ are generated when BACE1 cleaves APP, producing soluble APPβ (sAPPβ) and C99 fragments [27]. The γ-secretase complex then cleaves C99 to produce Aβ. Furthermore, in early-onset AD, mutations in presenilin-1 (PSEN1) and presenilin-2 (PSEN2) alter γ-secretase activity, increasing the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio by influencing the proteolytic function of γ-secretase [5].

3.2. Fibrillogenesis- Role of Aβ Plaque in AD

Aβ monomers combine to form oligomers, protofibrils, and amyloid fibrils, among other assemblies (Fig. 2). Whereas amyloid oligomers are soluble and can disperse throughout the brain, amyloid fibrils are larger, insoluble, and can further assemble into Aβ plaques [24]. Aβ monomers can exist as soluble oligomers capable of spreading within the brain or as large, insoluble fibrils that accumulate to form plaques. Because Aβ is involved in neurotoxicity and neuronal function, the buildup of dense plaques in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus can result in cognitive impairment, damage to axons and dendrites, synaptic loss, and stimulation of microglia and astrocytes [3].

Dual pathways of APP cleavage (non-amyloidogenic and amyloidogenic). This figure, adapted from [24], shows how the APP is processed by proteases at the cell membrane through both amyloidogenic and non-amyloidogenic pathways. APP is broken down by α-secretase at the extracellular domain in the non-amyloidogenic pathway, producing sAPPα and the membrane-bound CTFα (C83), which is then processed by γ-secretase inside the lipid bilayer to yield the P3 peptide and the AICD. AICD and Aβ peptides, particularly Aβ40 and Aβ42, are released when γ-secretase cleaves APP at a similar extracellular site in the amyloidogenic pathway, resulting in sAPPβ and CTFβ (C99). These occurrences highlight the membrane localization of APP metabolism [14, 19, 24].

Abbreviations: APP: Amyloid precursor protein; sAPPα: Soluble amyloid precursor protein-alpha; CTFα (C83): C-terminal fragment alpha (83 amino acids); P3: Peptide 3; AICD: APP intracellular domain; Aβ: Amyloid-beta; Aβ40: 40-amino-acid isoform of amyloid-beta; Aβ42: 42-amino-acid isoform of amyloid-beta; sAPPβ: Soluble amyloid precursor protein-beta; CTFβ (C99): C-terminal fragment beta (99 amino acids).

The formation of short, flexible, irregular protofibrils is the first step in fibrillogenesis. These protofibrils further aggregate to form a variety of oligomeric species, which eventually mature and elongate into insoluble fibrils with a β-strand-repeating substructure oriented perpendicular to the fiber axis, as described in Fig. (2) [28]. When Aβ aggregates extracellularly to form fibrils, it becomes resistant to proteolytic cleavage. Aβ monomers can assemble into oligomers and higher-order structures, with the β-sheet conformation allowing them to exist in a dynamic equilibrium of multiple structural states. To form unstable, soluble Aβ oligomers, Aβ40—or the more aggregation-prone Aβ42—first misfolds and then aggregates with additional monomers. Oligomeric amyloid represents an intermediary phase in the development of mature fibrils. AD is characterized by the accumulation of amyloid fibrils in extracellular plaques [26].

3.3. Aβ Interactions with Receptors

The cell membrane contains significant ion channels that maintain Ca2+ ion homeostasis within the cell. Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, including L-type, P-type, and Q-type, mediate the transport of these ions. Among these, the L-type channel is particularly relevant in AD due to its stimulatory capacity. When Aβ binds to specific synaptic receptors, it can activate these receptors, potentially leading to the opening of L-type Ca2+ channels. The relevance of the L-type channel lies in its ability to facilitate a significant influx of Ca2+ ions into the cell, which can influence various cellular processes. In the context of AD, excessive activation of these channels can contribute to neuronal dysfunction and cell death. However, in other situations, the cell may internalize and degrade the receptor–Aβ complex. This process can result in an increased concentration of Aβ peptide inside the cell, which may further disrupt cellular functions and contribute to the pathological effects observed in AD [29]. Additionally, Aβ can form complexes with different NMDA receptors. The NMDA receptor–Aβ interaction modifies the glutamate balance in neurons, resulting in excitotoxicity. This condition, known as excitotoxicity, occurs when excessive glutamate, an excitatory amino acid, becomes toxic to neurons [30]. As a result of this interaction, NMDA receptors become overactivated, leading to increased glutamate concentration in the synaptic cleft and causing excessive calcium influx. The resulting glutamate dysregulation increases the brain's excitatory signaling, overtaxing neurons and making them more susceptible to damage [31]. Thus, glutamate imbalance and the subsequent excitotoxicity play a pivotal role in exacerbating neurodegeneration in AD [5].

The aggregation and fibril formation of Aβ peptides. This figure, adapted from [28], depicts the sequential aggregation of Aβ peptides following APP processing. In the extracellular space, Aβ monomers are first produced and released, where they self-assemble into soluble oligomers. After interacting with the neuronal cell surface, these oligomers further assemble into linear protofibrils. Aβ plaques are formed when these protofibrils lengthen and solidify into insoluble fibrils that eventually accumulate close to neuronal membranes. AD pathology is significantly influenced by the accumulation of these aggregates at the cell surface, which may compromise membrane integrity and cellular function [26, 28].

Abbreviations: Aβ: Amyloid-beta; APP: Amyloid precursor protein; AD: Alzheimer’s disease.

The fibrillogenesis of Aβ oligomers depends on their binding to the ApoE isoform. Compared to the Aβ–ApoE3 complex, the Aβ–ApoE4 complex forms fewer stable complexes with Aβ, likely due to ApoE4's lower lipid content. ApoE4 also shows lower affinity for the LRP1 (Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 1) receptor and has a reduced rate of receptor endocytosis. Consequently, Aβ oligomers bound to ApoE4 undergo less receptor endocytosis and lysosomal degradation. Additionally, ApoE4 more effectively stabilizes extracellular amyloid oligomers, promoting their accumulation and the growth of Aβ plaques [29]. The α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7-nAChR) also plays a crucial role in AD, characterized by hyperphosphorylated tau protein and Aβ accumulations. Aβ binds to α7-nAChRs with high affinity, activating or inhibiting the receptor depending on the concentration. Evidence suggests α7-nAChRs are neuroprotective, reducing Aβ toxicity. However, the co-localization of Aβ, α7-nAChRs, and Aβ plaques implicates potential neurodegenerative effects [32].

3.4. Tau Protein

Tau protein binds to microtubules and belongs to the group of natively unfolded microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs). Its N-terminal region, proline-rich domain, microtubule-binding domain, and C-terminal region function in microtubule assembly, stabilization, and regulation of motor-driven axonal transport. Although tau is primarily found in neuronal axons, it may also be physiologically significant in dendrites [33, 34].

The tau protein is encoded by the microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) gene, which is predominantly expressed in neurons [35, 36]. An alternative splicing mechanism controls its expression during development, and the adult human brain contains six distinct isoforms. The alternative splicing of exons 2, 3, and 10 during tau transcription and translation produces these isoforms. It is important to remember that exon 3 can only be translated when exon 2 is present. The microtubule-binding domain's second repeat region (R2) is encoded by exon 10, and the N1 and N2 regions are encoded by exons 2 and 3 [34].

3.5. Modifications of Tau

It has long been known that tau's post-translational modifications alter its protein function and fuel neurodegeneration [37].

3.5.1. Hyperphosphorylation of Tau

The quantity of hyperphosphorylated tau in the AD brain is two to three times higher than in the healthy brain. Tau hyperphosphorylation is a result of the interaction between kinases and phosphatases. Proline-directed protein kinases (PDPKs) modify tau by phosphorylating it primarily on serine and threonine residues adjacent to proline. Tyrosine residues such as Tyr394 and Tyr18, which are found in Paired Helical Filaments (PHFs) in the brains of AD patients, are also phosphorylation targets. Tau can additionally be phosphorylated by several non-PDPKs, including casein kinase 1 (CK1), microtubule affinity-regulated kinase 110 (MARK p110), calcium/calmodulin-activated protein kinase II (CaMK II), and protein kinase A (PKA) [38].

Tau dephosphorylation has been linked to protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), PP2A, PP2B, PP2C, and PP5, with PP2A being the primary phosphatase among them. Since hyperphosphorylation and aggregation are both elevated in AD, hyperphosphorylated tau may cause pathology through several mechanisms. For example, it may cause tau to mis-sort from axons to the somatodendritic compartment, resulting in synaptic dysfunction, impaired proteasome function, and tau aggregation [38, 39].

3.6. The Role of a Higher Amount of Tau Protein in AD

A rise in tau can be caused by a deficiency in tau degradation, an increase in the translation of tau protein, or an increase in the transcription of the MAPT gene. Currently, the working hypothesis is that inadequate protein degradation, rather than increased tau expression, is the primary cause of tau accumulation. When tau protein is not broken down by the body, it can be phosphorylated by different kinases or undergo other modifications that lead to the buildup of modified tau. When these altered forms accumulate in neurons, some of them become toxic and can cause neuronal degeneration in AD [40].

Diseases known as tauopathies are caused by malfunctions in the tau protein, either through a decline in function or the acquisition of toxic function. Tau undergoes various post-translational modifications under physiological conditions, which affect the structure, functionality, and intracellular processing of the protein. Since phosphorylation is thought to play a key role in tau pathology, it has drawn the most attention. It has been suggested that cytosolic accumulation of phospho-tau occurs before tau aggregation, which causes neuronal degeneration in AD and tauopathies [36, 40].

The dynamics and equilibrium of tau-microtubule binding are significantly influenced by its aberrant post-translational modifications, such as acetylation and hyperphosphorylation. After aggregating in the cytosol, these changes alter its conformation, resulting in the formation of NFTs. The formation of NFTs is more closely associated with cognitive decline than the distribution of senile plaques, an additional pathological feature of AD formed by polymorphous Aβ protein deposits [38].

Axons, dendrites, and neuronal perikaryon cytoplasm are all affected when the tau protein that is not normally phosphorylated begins clumping together in filaments known as NFTs, which are primarily composed of bundles of Paired Helical Filaments (PHFs). This leads to the loss of tubulin-associated proteins and cytoskeletal microtubules in the neuronal perikaryon cytoplasm. However, both adult and fetal brains exhibit normal tau phosphorylation without aggregation into filaments. Moreover, under physiological conditions, recombinant non-phosphorylated tau forms filaments when combined with various polyanions, indicating that pathological filament formation is promoted by mechanisms other than aberrant phosphorylation [3-41].

Tau's intrinsic disorder is primarily caused by the high concentration of basic amino acid residues in its primary structure. Therefore, phosphorylation or interactions with anionic species are required to neutralize the excess positive charge on tau molecules. Tau filaments are induced to form by anions such as taurine, docosahexaenoic acid, and arachidonic acid. To induce the formation of tau filaments, poly-L-glutamic acid and heparin—powerful polyanionic inducers of tau fibrillization—can also be used to promote tau aggregation. Of these, heparin is the most frequently studied [42].

3.7. Role of Aβ on Neurofibrillary Degeneration

NFTs and extracellular amyloid deposits are the two main neuropathological elements associated with AD. NFTs arise due to the abnormal phosphorylation of tau isoforms, which subsequently accumulate and aggregate into fibrils within neurons. NFTs influence the cholinergic system in AD, and there is a substantial relationship between cognitive deficits and their spatiotemporal distribution. Furthermore, there is a correlation between the advancement of tau pathology and elevated levels of brain Aβ peptides, as well as the disappearance of APP metabolites [43].

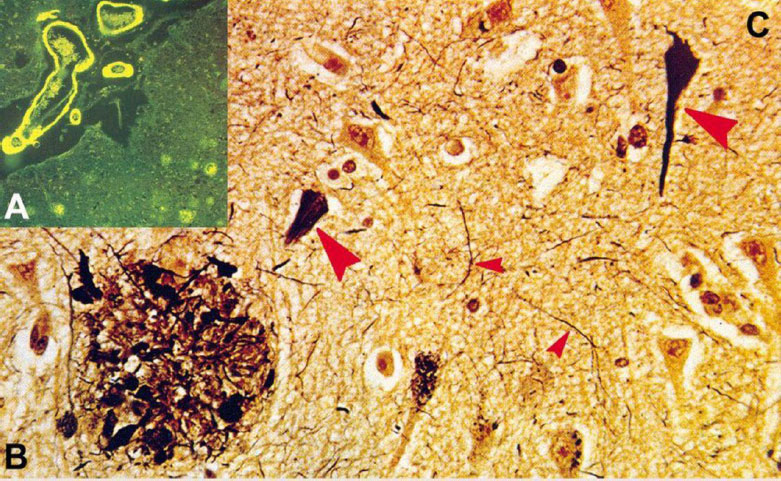

A growing body of data indicates that APP metabolism controls tau expression by inhibiting β-secretase, which lowers intracellular tau protein (cleavage by β-secretase releases a soluble APP fragment into the extracellular space). The intersection of tau metabolism and APP may be found in the cellular protein homeostasis systems that are controlled by autophagy and the endosome/lysosome pathways [44, 45]. These alterations are shown in Fig. (3) (adapted from [46, 47]), which illustrates characteristic histopathological changes, including amyloid deposits, neuritic plaques, and tau-associated neurofibrillary tangles.

3.8. Cholinergic Neurons in AD

A neurotransmitter called acetylcholine (ACh), released by cholinergic neurons, plays a central role in signal transduction mechanisms related to memory and learning. The cholinergic theory—the earliest proposed explanation for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathophysiology—arose from observations that cholinergic neurons are involved in cognitive decline and behavioral impairments associated with AD. Abnormalities in central cholinergic function can contribute to apoptosis, neuroinflammation, aberrant tau phosphorylation, and other pathological processes [48].

Histopathological images depicting the pathogenesis of AD. This figure, adapted from [46], illustrates the histopathological changes characteristic of AD, including: (A) Congo red-stained amyloid plaques in the neuropil, which are used to identify amyloid deposits [46]; (B) Neuritic plaque with dystrophic neurites revealed by Bodian stain, which accentuates neuronal processes and structural abnormalities [47]; and (C) neurofibrillary tangles (big arrows) and neuropil threads (small arrows), which are also shown by Bodian stain, indicating the presence of pathological filamentous tau aggregates within neurons [46, 47].

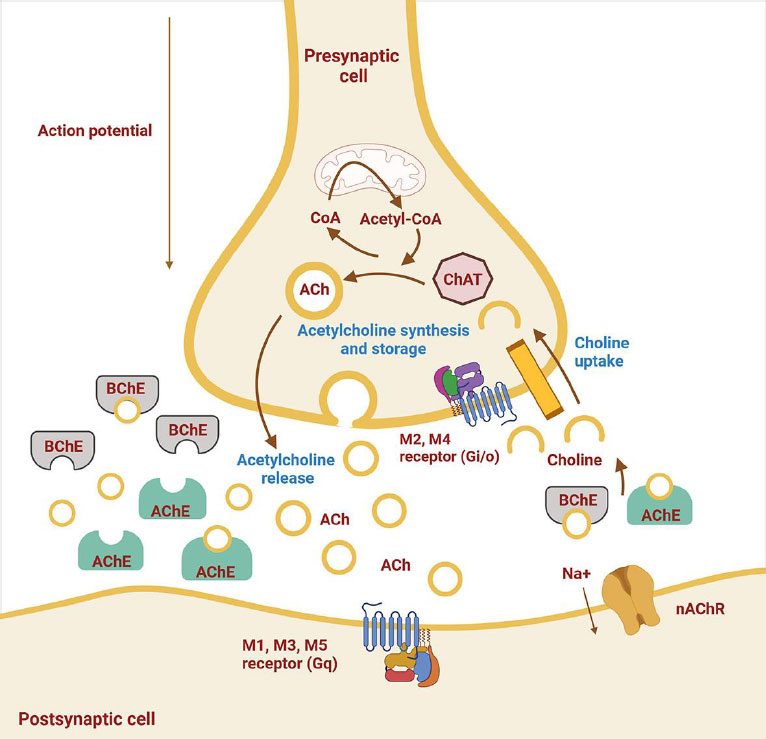

Cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain are particularly vulnerable to neurofibrillary degeneration and neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) formation. Reduced activity of choline acetyltransferase (the enzyme responsible for ACh synthesis) (Fig. 4) [49] correlates with increasing neuritic plaque burden in AD brains, suggesting a link between cholinergic dysfunction and Aβ pathology. Animal studies support this connection, showing that cholinergic loss is associated with increased Aβ deposition and elevated levels of hyperphosphorylated tau in the cortex and hippocampus [50]. Additional contributors to cholinergic impairment include reductions in nicotinic and muscarinic (M2) acetylcholine receptors located on presynaptic cholinergic terminals. These receptor deficits diminish glutamate levels and D-aspartate uptake across multiple cortical regions in AD [3].

Although cholinergic dysfunction in AD is most pronounced in regions critical for learning and memory—particularly the basal forebrain—other cholinergic systems (e.g., those in anterior horn cells and motor brainstem nuclei) appear to be comparatively preserved [51]. Electrophysiological studies indicate that peripheral nerve conduction and motor evoked potentials do not differ significantly between AD patients and healthy controls, suggesting intact motor neuron function. This preservation may be due to differing neurotransmitter dependencies; for instance, the corticospinal tract primarily uses glutamate rather than acetylcholine, rendering it less susceptible to cholinergic deficits characteristic of AD [52]. Emerging evidence also suggests reduced vulnerability of cholinergic neurons in these motor-related regions, though their precise contribution to AD pathology remains unclear [53].

Cholinergic system alterations in AD. This figure, reproduced from [49], shows neurotransmitter release and receptor changes. ACh is synthesized by the enzyme ChAT within the presynaptic neuron. Once released into the synaptic cleft, ACh exerts its effects on the postsynaptic neuron by binding to muscarinic (M1-M5) and nicotinic receptors. The enzyme AChE in the synaptic cleft breaks down ACh, terminating its action. Overexpression of AChE leads to a decrease in ACh levels, which is associated with the development of AD [48, 49]. Abbreviations: ACh: Acetylcholine; ChAT: Choline acetyltransferase; AChE: Acetylcholinesterase; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; M1–M5: Muscarinic receptor subtypes 1 to 5.

Despite its historical importance, the cholinergic hypothesis alone cannot fully account for AD complexity. Some early-stage patients demonstrate normal or even elevated acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity, suggesting that cholinergic deficits may arise later in disease progression and may not be the initiating pathological event [50]. Furthermore, the modest and transient benefits of cholinesterase inhibitors imply that multiple neurotransmitter systems—including dopaminergic, glutamatergic, and serotonergic pathways—also play significant roles in cognitive decline [54]. These findings underscore the need for a broader, multi-system framework when examining the neurochemical basis of AD.

3.9. Oxidative Stress

ROS, reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and other free radical species build up excessively inside cells and cause oxidative stress, which aids in the development and progression of various diseases [50]. In neurodegeneration and AD, oxidative damage products—such as those resulting from the oxidation of lipids, DNA, RNA, or advanced glycation end-products—have been proposed as biomarkers. These molecules can be found in bodily secretions such as blood, serum, plasma, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), urine, and saliva. It is crucial to determine whether these molecules are present in peripheral circulation and whether they are useful as AD biomarkers. When there is an imbalance in the levels of pro-oxidants and antioxidants, this imbalance can lead to oxidative stress and the destruction of biological molecules linked to AD [55, 56]. Due to its high metabolic activity and high susceptibility to ischemic damage, the brain is particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage. Thus, oxidative stress is crucial to the pathophysiology of AD [57].

Free radicals like ROS and RNS contain one or more unpaired electrons in their outermost shell, making them unstable and highly reactive. ROS and RNS are byproducts of regular cellular metabolism. Numerous pathways and sources can lead to the endogenous production of ROS and RNS. Many enzymes in various subcellular compartments can also produce ROS and RNS, even though the mitochondrial electron transport chain is usually the main source of endogenous reactive species formation [57]. Under both normal and pathological circumstances, mitochondria are the primary source of ROS, and O2•− can be produced during cellular respiration. It is important to note that even though these organelles have an innate capacity to salvage ROS, this is insufficient to meet the cell’s need to eliminate the quantity of ROS that mitochondria produce. Mitochondrial dysfunction in AD further exacerbates ROS production, as impaired mitochondrial function leads to increased leakage of electrons during oxidative phosphorylation, contributing to the accumulation of ROS [58]. Oxidative damage may arise from excessive ROS generation, a condition known to harm cells and tissues and disrupt signaling pathways [57, 59].

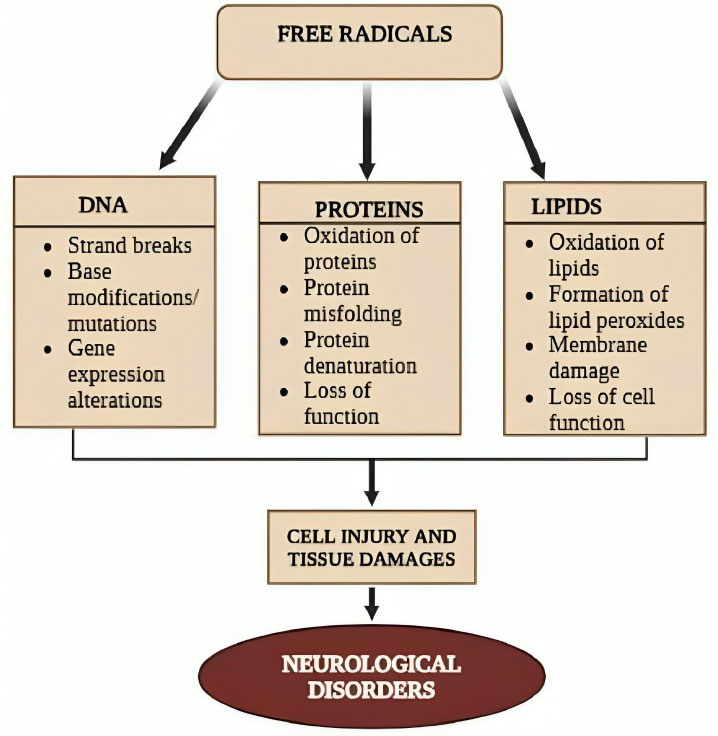

Antioxidant defenses and ROS-generating cellular processes keep ROS in a dynamic equilibrium. When ROS overwhelms the antioxidant defense mechanisms, oxidative stress occurs. This breakdown in homeostasis results in excessive ROS production or a decrease in defense systems, contributing to cellular dysfunction and damage [60]. The excessive production of ROS and/or a reduction in antioxidant defenses may be linked to the neurodegeneration seen in AD (Fig. 5) [60]. When Aβ deposition interacts with mitochondria or microglial surface receptors, it can also directly cause an increase in ROS. In the AD brain, oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, mitochondrial DNA, RNA, and other components has been reported [56]. ROS production may be caused by elevated levels of iron and other metals; iron has also been linked to ferroptosis. Additionally, changes in Ca2+ influx and the resulting mitochondrial dysfunction are also essential contributors to oxidative damage. Diminished concentrations of distinct lipids have been associated with cognitive impairments in AD, indicating their potential application as biomarkers in AD [56, 60].

3.10. Oxidative Damage and Inflammation in AD

Pathologic indicators of neurodegeneration include oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. ROS are produced in the central nervous system by innate immune cells, and an alternative mechanism for AD-related neuronal damage is the overproduction of oxidants [61]. Neuroinflammation is the general term used to describe the way the central nervous system (CNS) reacts to injury and disease. Within this response, both neural and non-neural cells work in concert to initiate cascades. The complex and diverse structure of the CNS makes it easy to understand how even a small imbalance in any one of its parts could have unintentional effects that hinder rather than help the CNS recover from injury. CNS injury can lead to the production of pro-inflammatory neurotoxic molecules (interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, tumour necrosis factor-α, and transforming growth factor-β), all of which can promote AD pathogenesis [62]. Activated microglia in the early stages of AD facilitate pathologic Aβ or tau clearance and phagocytosis, which have a positive impact on AD pathologies. However, persistent microglial activation increases the release of inflammatory factors and impairs their capacity to phagocytose and break down neurotoxins. This exacerbates Aβ accumulation, tau propagation, and neuronal death, ultimately accelerating the progression of AD [63].

Understanding how inflammation and oxidative stress interact in AD is essential to comprehending how AD develops. Oxidative stress and inflammation in AD are closely related, resulting in a vicious cycle that speeds up neurodegeneration [12]. Excess ROS production causes lipid peroxidation, protein modification, and DNA damage, which in turn trigger inflammatory responses. These processes are brought on by a number of factors, including mitochondrial dysfunction, environmental stressors, and glial cell activation [59]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are released during these inflammatory responses, which are mainly mediated by microglia and astrocytes, and these cytokines can further increase the production of ROS [64]. The increased ROS levels worsen microglial activation, resulting in persistent inflammation that hinders the glial cells' capacity to eliminate neurotoxic proteins such as tau and Aβ [59]. This accelerates neuronal damage and cognitive decline in AD by generating a feedback loop of inflammation and oxidative damage [56]. Furthermore, the chronic nature of neuroinflammation in AD is largely due to oxidative stress, which intensifies the activation of particular receptors, such as the Toll-like Receptors (TLRs) on microglia, which sustain the inflammatory response [65]. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) elicit a response from TLRs, also known as pattern recognition receptors. Several TLRs are expressed in the CNS, primarily in microglia and astrocytes, and these receptors initiate signaling cascades as a defence mechanism through the sustained immune homeostasis-induced synthesis of pro-inflammatory molecules resulting from TLR overactivation [66].

The combined findings of these studies highlight the involvement of oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in AD pathology by showing that they are consistently elevated in AD patients across a range of sample types. A description of these markers, the sample types used for their analysis, and the significant findings connected to each are given in Table 1 [67-78].

3.11. Stages of Ad

The clinical phases of AD can be classified into:

(a) Pre-clinical, also known as the pre-symptomatic stage, which may extend over several years. At the pre-clinical phase, there are currently no clinical signs or symptoms of AD, except for mild memory loss, early pathological alterations in the cortex and hippocampus, or functional impairment in day-to-day activities.

(b) The mild or early stage of AD is defined by symptoms such as trouble focusing and remembering details, disorientation regarding location and time, mood fluctuations, and the onset of depression.

(c) AD in its moderate stage has progressed to regions of the cerebral cortex, resulting in more severe memory loss, inability to recognize friends and family, loss of impulse control, and difficulties with speaking, writing, and reading.

(d) Severe AD, also known as late-phase AD, is characterized by a progressive loss of function and cognition, including the inability to recognize family members, bedridden status, difficulty swallowing and urinating, and ultimately death from these complications. Neuritic plaques and NFTs, a severe accumulation of the disease, spread throughout the entire cortex area [3].

| Oxidative Stress Biomarkers | Inflammatory Biomarkers | Sample Type | Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-OHdG, 8,12-iso-iPF2α VI, F2-IsoPs, Protein Carbonyls | IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, PGF2α | CSF | • The CSF of AD patients had higher levels of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, but IL-1β did not differ from controls [67]. • In AD, 8-OHdG was higher in CSF than in controls [68]. • In contrast to patients with MCI, A+ patients have higher p-tau levels in the presence of 8,12-iso-iPF2α VI [68]. • As the disease progressed, F2-IsoPs rose in CSF in the early stages of AD [68, 69]. • There was no significant difference in protein carbonyl levels between AD patients and controls [68]. • In patients with A+ MCI, PGF2α is linked to elevated p-tau levels [68]. |

[67-69] |

| 8-OHdG, MDA, F2-IsoPs, Protein carbonyls | IL-6, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-18, TNF-α, GFAP | Blood | • Chronic inflammation is suggested by elevated blood levels of IL-1β, IL-2, and IL-18; IL-1β is associated with microglial activation and neurodegeneration, while IL-2 and IL-18 are involved in the inflammatory response [70]. • Compared to controls, AD patients' lymphocytes had a higher concentration of 8-OHdG [71]. • Elevated plasma MDA levels are observed in AD, although these levels are influenced by external factors such as exercise and smoking [71-73]. • F2-IsoPs results on plasma are inconsistent [72]. Higher plasma levels of protein carbonyl are reported in AD [73]. • An inflammatory response in AD compared to controls is indicated by higher plasma levels of IL-6 in A+ versus A– individuals [73]. • In AD, TNF-α levels in blood are markedly elevated [73]. • Compared to healthy elderly individuals, subjects with preclinical AD have significantly higher plasma levels of GFAP [74]. |

[70-74] |

| MDA and TBARS, Acrolein, F2-IsoPs, 8-OHdG, Protein carbonyls | IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, TGF-β1 | Brain tissue | • The brains of AD patients have higher levels of TBARS and MDA [75]. • Higher levels of protein carbonyl are found in AD brains [72, 75]. • Higher levels of 8-OHdG in the brain are reported in AD [72, 75, 76]. • AD is associated with elevated acrolein levels [75]. • Increased IL-1 levels in the AD brain are associated with tau phosphorylation, neurofibrillary tangles, and the development of Aβ plaque [77]. • Early-stage plaque formation is correlated with elevated IL-6 in the AD brain [77]. • In AD, the brain has higher levels of F2-IsoPs [75]. • The AD brain has higher levels of TNF-α, which is linked to apoptosis, neuronal toxicity, and cognitive decline [77]. • In AD, microglial activation, neuroinflammation, and cognitive decline are all influenced by TGF-β1 deficiency. Cerebrovascular Aβ deposition is correlated with elevated levels seen in the brain and CSF [78]. |

[72, 75-78] |

3.12. Familial and Sporadic AD

While familial AD is known as early-onset and is typically inherited in a Mendelian manner, sporadic AD is typically referred to as late-onset. A very uncommon, early-onset, autosomal-dominant disease, familial AD may occur due to mutations in the presenilin gene and APP, two genes involved in the metabolism of Aβ. Sporadic AD is much more common than familial AD, affecting over 15 million people globally [19].

4. CONDITIONS THAT INFLUENCE AD

AD pathogenesis is influenced by multiple factors, including aging, environmental factors, health conditions, and heredity.

4.1. Aging

One of the biggest risk factors for AD is aging, as younger individuals are not frequently affected by this illness. The majority of AD cases develop later in life, typically beyond the age of sixty-five. Aging is a multifaceted, irreversible process that affects many organs and cell systems, where brain volume and mass decrease, synapses are lost, and ventricles enlarge in specific areas, accompanied by NFTs and Aβ deposits [3]. The likelihood of experiencing cognitive decline is negatively correlated with leading an active physical life. Physical activity is the most widely used approach to investigating how exercise can lessen the negative effects of aging on cognitive performance and is crucial in halting disease progression in older adults through aerobic exercise combined with cognitive stimulation [79].

4.2. Physical and Environmental Factors

It has been documented that sleep instabilities increase levels of Aβ in the brain fluid of healthy individuals, thereby facilitating neurodegeneration and the emergence of mild cognitive decline [80]. Increased light exposure during the sleep–wake cycle raises insoluble tau levels and impairs memory by inhibiting melatonin, the hormone that regulates sleep–wake cycles. Consequently, irregular sleep patterns have emerged as significant risk factors for AD development and must be appropriately treated with medications that restore physiologically normal sleep cycles [80].

Diet also plays a role in AD pathology. Both deficiencies and excesses of dietary compounds contribute to risk. AD may arise due to deficiencies in antioxidants such as vitamins E and C, folates, and vitamins B6 and B12. Antioxidant vitamins inhibit oxidative stress and Aβ-induced lipid peroxidation, as well as inflammatory signaling cascades [81].

Furthermore, smoking may raise the risk of AD by generating free radicals, elevating oxidative stress, and stimulating the immune system’s pro-inflammatory response through phagocyte activation. These effects can lead to cerebrovascular diseases, which in turn elevate AD risk [81].

4.3. Health Conditions

AD and hypertension are interrelated. The relationship is driven by cerebrovascular disease, as hypertension alters vascular walls, causing cerebral ischemia, which leads to the accumulation of Aβ and the eventual development of AD [80]. Obesity is also widely recognized to increase the risk of type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative illnesses such as AD. Chronic obesity-related hyperglycemia increases Aβ accumulation, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation via the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, ultimately contributing to cognitive impairment [3].

Additionally, research has shown a connection between depression and elevated Aβ deposition in patients [81]. Neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine play important roles in AD pathophysiology as well as depression. These neurotransmitters may be crucial in the progression of AD stemming from depression. While dopamine loss damages memory, dopamine release improves cognitive function. Depression is characterized by low serotonin levels and reduced dopamine production [82].

4.4. Genetic Risk Factors

AD can be divided into groups based on when the first symptoms manifest. About 4–6% of AD cases are early-onset, affecting individuals below 65 years, whereas late-onset AD affects those above 65 years [83]. Late-onset AD is primarily associated with a polymorphism in the APOE gene, specifically the presence of the ε4 allele, whereas early-onset AD typically results from fully penetrant mutations in PSEN1, PSEN2, and APP [83].

The APP gene, located on chromosome 21q21, has been linked to more than 30 dominant mutations, accounting for 15% of early-onset autosomal dominant AD cases [61]. When APP is cleaved, many Aβ peptides are produced; the most prevalent is Aβ1–42, which is primarily found in senile plaques. The more soluble Aβ1–40 is associated with cerebral microvessels and may appear later in the disease. Depending on the mutation type, soluble peptide oligomers may also play a role, providing a genetic basis for variations in familial AD pathophysiology [84].

ApoE is a glycoprotein involved in lipid metabolism and is highly expressed in brain and liver astrocytes, as well as certain microglia. It is encoded by the APOE gene on chromosome 19. Three ApoE alleles (ε2, ε3, and ε4) produce the ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4 isoforms, respectively [3, 84]. The ApoEε4 allele poses a substantial risk for both early-onset and late-onset AD, whereas ApoEε2 has a protective effect, and ApoEε3 is neutral. ApoEε4 promotes senile plaque formation of Aβ and contributes to cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), a marker associated with AD [3].

5. THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES IN AD

The goal of therapeutic approaches for AD is to reduce symptoms and delay the disease's progression.

5.1. Symptomatic Treatment of AD

Among the most established and time-tested theories regarding the pathophysiology of AD is the cholinergic hypothesis. ACh is an excitatory neurotransmitter involved in cognitive behaviours and is regulated by the cholinergic nerve network. According to this theory, the pathophysiology of AD is accompanied by the loss of cholinergic functions in different brain regions, including the hippocampus and cortex [85]. Inhibiting AChE is one method to raise cholinergic levels, which is thought to improve brain and neural cell function. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) block the breakdown of ACh in synapses, resulting in its sustained accumulation and continued cholinergic receptor activation [3].

Cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA-receptor antagonists are part of currently approved therapies; however, while their combination can provide more than momentary symptom relief and may extend a patient’s retention of cognitive function for several months, their impact on long-term disease progression remains limited [86]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved tacrine as the first AChEI for AD treatment. This drug increases ACh in muscarinic neurons. However, due to a high frequency of side effects, including hepatotoxicity, documented in multiple trials, it was withdrawn from the market. Currently, the FDA has approved rivastigmine, donepezil, and galantamine as AChE inhibitors, as well as the NMDA antagonist memantine [3]. The most frequent side effects of these medications are gastrointestinal—such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and anorexia—although most patients tolerate them. Memantine, a non-competitive NMDA antagonist, reduces glutamate-induced excitatory neurotoxicity and has demonstrated modest efficacy and safety in moderate to severe AD. When combined with AChE inhibitors, memantine provides additional benefits compared with monotherapy [87].

5.2. Donepezil

Donepezil, a piperidine AChE inhibitor, is commonly prescribed to treat AD [88]. By reversibly binding to AChE and inhibiting ACh hydrolysis, donepezil increases ACh levels at synapses. The medication has mild and temporary cholinergic side effects related to the nervous and gastrointestinal systems, but is generally well tolerated. Donepezil improves symptoms of AD—such as behaviour and cognition—without slowing disease progression [3].

Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) strengthens synaptic and cognitive functions. Curcumin, often delivered using nanocarriers to improve effectiveness, possesses neuroprotective properties in various CNS disease models and can cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Combined treatment with donepezil and curcumin has shown synergistic effects in AD by modulating the GSK-3β pathway, which otherwise promotes Aβ accumulation and tau phosphorylation, leading to memory impairment [89].

5.3. Galantamine

Galantamine is a phytochemical alkaloid capable of crossing the BBB and increasing central cholinergic tone. It also reversibly inhibits AChE activity [90]. This tertiary isoquinoline alkaloid acts selectively in two ways: it binds allosterically to the α-subunit of α7-nAChR to activate it, and it competitively inhibits AChE [3].

Galantamine is considered an initial therapy for mild to moderate AD; however, due to its limited efficacy and potential side effects with continuous use, combining GAL with other compounds has been suggested. One such compound is fisetin, found in fruits and vegetables, which reversibly and effectively inhibits both butyrylcholinesterase and AChE in vitro [91].

5.4. Rivastigmine

Rivastigmine, a phenyl-carbamate derivative, functions as a dual inhibitor of butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) and AChE. BuChE is not inhibited by galantamine or donepezil. Because BuChE levels rise in the hippocampus and temporal cortex of AD patients as the disease progresses, while AChE activity decreases, rivastigmine’s ability to inhibit both enzymes involved in ACh hydrolysis may have important clinical implications. Dual inhibition increases the brain’s ACh levels [92]. Adverse effects—including nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, asthenia, anorexia, and weight loss—are associated with oral rivastigmine administration. Although tolerable, these side effects are a common reason for discontinuation [3, 92].

5.5. Targeting Aβ

The amyloid cascade hypothesis assumes that the primary cause of the neurodegenerative process of AD is the accumulation of Aβ peptide and its subsequent aggregation and deposition in the form of Aβ plaques [87]. Approaches to target Aβ in AD include modulating β-secretase activity, using γ-secretase modulators, preventing Aβ aggregation, or clearing Aβ to reduce its production [93].

5.6. β-Secretase Inhibitor

Inhibitors of β-secretase primarily lower the amount of Aβ produced [93]. It is known that the production of Aβ42 is restricted by the inhibition of BACE [87, 93]. Although many BACE1 inhibitors have recently been developed, only five—verubecestat, lanabecestat, atabecestat, umibecestat, and elenbecestat—have advanced to Phase III clinical trials. All five medications effectively lowered Aβ levels in the CSF of AD patients. However, due to the lack of cognitive or functional benefit, these compounds were discontinued, and in some cases, a decline in cognitive function was observed [87].

5.7. Gamma (γ)-Secretase Inhibitor

A γ-secretase inhibitor cleaves multiple substrates, including amyloid. The γ-secretase complex plays a physiological role in sustaining neuronal development by contributing to the differentiation of neuronal cells and preserving a reservoir of neural progenitor cells [94]. Semagacestat, a non-selective small-molecule γ-secretase inhibitor, decreases Aβ deposition through the same mode of action as β-secretase inhibitors [93, 94]. Apart from the risks of skin cancer and weight loss, Phase III clinical trials for semagacestat were terminated early because patients with AD began to exhibit marked cognitive decline. Another γ-secretase inhibitor, avagacestat, also failed to demonstrate promising outcomes in AD [86].

5.8. Inhibiting the Formation of Aβ Aggregation

After amyloid monomers group together to form hazardous oligomers, β-sheets are formed, eventually accumulating as plaques in the extracellular matrix [94]. Several medicinal compounds have been developed to specifically target and prevent amyloid aggregation. Early clinical trials showed promising results for two drugs, tramiprosate and colostrinin. Tramiprosate, an amino acid naturally found in seaweed, modulates GABA receptors to exert neuroprotective effects. By preventing glycosaminoglycan binding to Aβ, it inhibits Aβ aggregation and β-sheet formation. However, its Phase III trials did not yield the anticipated positive outcomes. Colostrinin, a proline-rich polypeptide extracted from ovine colostrum, has been shown to prevent Aβ aggregation by influencing the innate immune system, but it also did not produce encouraging results in Phase II trials [86, 94].

5.9. Immune-based Therapies: Elimination or Clearance of Amyloid Clusters

Since Aβ accumulation and aggregation are considered the primary cause of the neurodegenerative process in AD, targeting Aβ clearance with specific anti-Aβ antibodies is a logical strategy. Immunotherapy directed at Aβ is one of the most effective methods to slow AD progression. This therapy can be categorized into active and passive immunotherapies [87].

5.9.1. Active Immunotherapy (Vaccine)

Active immunotherapy stimulates the body’s immune system to generate antibodies against Aβ by injecting the protein or its fragments [87]. The first anti-Aβ vaccine (AN1792) demonstrated that Aβ plaques could be effectively eliminated by active immunotherapy, with effects lasting up to 14 years. However, meningoencephalitis (ME) occurred in approximately 6% of AD patients receiving AN1792 in the Phase IIa trial, leading to its termination [95]. This adverse effect was attributed to a T-cell–mediated immune response. Despite this, AN-1792 showed positive outcomes in clearing amyloid plaques from the brain [87-95].

To address these issues, a novel vaccine, ACC-001, was developed to accelerate Aβ plaque removal while avoiding harmful T-cell responses. Phase II clinical trials of ACC-001 in individuals with mild to moderate AD demonstrated acceptable safety regardless of the inclusion of the QS-21 adjuvant. Furthermore, ACC-001 + QS-21 generated higher anti-Aβ antibody levels compared to the group without QS-21 [93]. ACC-001, which uses a carrier protein, an active saponin adjuvant (QS-21), and a short Aβ fragment, is currently in a long-term Phase II trial with promising results [95].

5.9.2. Passive Immunotherapy

Passive immunotherapy involves administering monoclonal antibodies or immunoglobulins [86]. Six antibodies—BAN2401, solanezumab, crenezumab, gantenerumab, aducanumab, and bapineuzumab—have entered Phase III clinical trials. Although most monoclonal antibodies have shown the ability to reduce CSF biomarker levels and Aβ plaques, only a few have demonstrated clinical efficacy [87]. Monoclonal antibodies targeting Aβ in randomized clinical trials have been associated with MRI-detected abnormalities known as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) [96]. In clinical trials, both lecanemab and donanemab slowed AD-associated cognitive decline. Lecanemab, approved in the United States, is specific for early AD with confirmed brain amyloid pathology [97]. Lecanemab, a high-affinity monoclonal antibody for large, soluble Aβ protofibrils, demonstrated robust efficacy and manageable risk in Phase II trials and is currently in Phase III [98]. Approved by the FDA in January 2023, it reduces Aβ accumulation and slows cognitive decline, with significant improvements across multiple clinical measures. Common adverse effects include headache, infusion reactions, and ARIA [99]. Similarly, donanemab reduced brain Aβ plaques and significantly slowed disease progression in early symptomatic AD. Participants treated with donanemab had a reduced risk of progressing to the next disease stage. Adverse effects included ARIA and some infusion-related reactions [100].

5.10. Targeting Tau

The two mechanisms responsible for both increased neuronal loss and the development of NFTs are tau deposition and phosphorylation [86].

5.10.1. GSK-3β Inhibitor

It is possible to regulate increased tau phosphorylation by blocking the GSK-3 enzyme [86]. Evidence supports the use of GSK-3β inhibitors, such as lithium, in AD therapeutics by demonstrating that GSK-3β overactivity mediates tau hyperphosphorylation [94]. Lithium inhibits GSK-3 and also affects glial cell function, glucose metabolism, and cell signaling and proliferation. Lithium can prevent tau hyperphosphorylation and amyloid production, and certain case reports and case-control studies have demonstrated that lithium can lessen AD symptoms. However, prolonged use of clinically available lithium is associated with serious adverse effects [93].

5.10.2. Inhibition of Tau Aggregation

In AD, the growth and accumulation of tau aggregates are linked to neuronal loss and functional impairment [87]. Hydromethanesulfonate and methylthioninium chloride are examples of tau aggregation inhibitors capable of reducing tau accumulation [93]. The ability of methylthioninium, a member of the diaminophenothiazine class of compounds, to inhibit tau aggregation has been investigated [94]. However, in a Phase II study, methylthioninium chloride did not demonstrate clinical benefit in AD. Additionally, a Phase II hydromethylthionine trial in mild-to-moderate AD was abruptly stopped for administrative reasons [93].

5.11. Drugs Targeting Neuroinflammation

Numerous NSAIDs (Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs) have been investigated. One of the most widely used NSAIDs is ibuprofen, and studies have shown that it may improve cognitive impairment [101]. It has been observed that administering oral ibuprofen to mice that overexpress human APP lowers total brain Aβ levels, plaque burden, and neuroinflammation [102]. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is another commonly used analgesic and antipyretic that has been demonstrated in mice to exert neuroprotective, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects. It also appears to improve cognitive impairment by blocking the mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) pore and the subsequent apoptotic pathway [101].

However, there is a risk of adverse effects with both acetaminophen and ibuprofen, especially when they are used frequently or in high doses [103]. In particular, in the elderly population, long-term ibuprofen use has been linked to gastrointestinal problems such as bleeding and ulcers [104]. Furthermore, some research indicates that long-term NSAID use may not improve cognition and may even worsen cognitive decline due to adverse side effects [104, 105]. Likewise, although acetaminophen is generally regarded as safe when taken as prescribed, prolonged or excessive use can cause hepatotoxicity and has been associated in certain observational studies with a higher risk of cognitive impairment. Therefore, even though these drugs might have neuroprotective effects in some situations, their possible side effects make them risky to use, especially in individuals who are at risk of AD [106, 107].

5.12. Role of Functional Food-based Strategies in the Treatment of AD

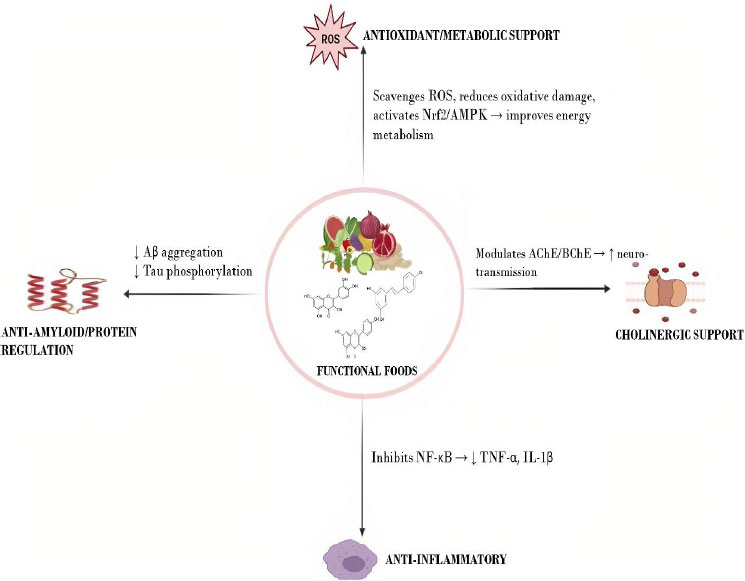

There is currently no effective treatment for AD. This calls for the identification of viable and more effective treatments that specifically target pathological features of AD. AD remains progressive and incurable despite massive efforts to find a cure. Studies indicate that consuming antioxidant-rich foods may lower the risk of AD by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which play critical roles in its onset and progression [10]. Functional foods, rich in bioactive compounds, have gained attention for their potential to modulate the oxido-inflammatory balance in AD (Fig. 6) [2, 10]. Preventing the excessive production of ROS and modulating inflammatory pathways may therefore represent a promising strategy to counteract the onset and progression of AD, thus offering a potentially useful approach for AD management [2]. The current review provides an overview of the medicinal potential of various bioactive compounds present in functional foods in this respect.

5.12.1. Quercetin

This naturally occurring flavonoid, quercetin, is present in many foods, such as tea, apples, berries, grapes, onions, and other fruits and vegetables [108]. The complex neuroprotective properties of quercetin have attracted significant interest. Its capacity to alter oxidative stress, inflammation, and other pathological pathways linked to AD is what gives it therapeutic potential [109].

Quercetin has strong antioxidant properties that improve endogenous antioxidant defenses and efficiently scavenge ROS. It induces the upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), an essential enzyme in cellular defense against oxidative damage, by activating the Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2–Related Factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway [109, 110]. In addition to lowering oxidative stress, this activation also has anti-inflammatory effects by blocking the Nuclear Factor-Kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway, which reduces the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-1β [111]. Moreover, quercetin has been demonstrated to alter the activity of key enzymes that regulate neurotransmitters, including BuChE and AChE, which may improve cognitive function by boosting cholinergic transmission [112].

Furthermore, quercetin improves mitochondrial function and energy metabolism by activating the AMP-Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK) pathway [113]. In animal models of AD, preclinical research has shown quercetin's effectiveness in reducing neuropathological alterations and improving cognitive deficits [114]. For example, administering quercetin to transgenic mice improved memory function, decreased neuroinflammation, and reduced Aβ plaque formation. In triple-transgenic Alzheimer's disease (3xTg-AD) mice, performance on cognitive tests such as the elevated plus maze test showed that quercetin treatment significantly improved spatial learning and memory. Additionally, it significantly decreased neuroinflammatory markers in the hippocampus and amygdala, such as microgliosis and astrogliosis, as shown by a decrease in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunoreactivity, suggesting suppressed astrocyte activation. Furthermore, quercetin treatment resulted in a notable reduction in extracellular β-amyloidosis in these brain areas, as evidenced by decreased levels of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 peptides, as well as a decrease in BACE1-mediated cleavage of APP, a crucial stage in the development of Aβ plaque [115-117].

Frequent ingestion of these foods may have neuroprotective effects and help delay or prevent the onset of AD. However, because of its rapid metabolism and poor absorption, quercetin has relatively low bioavailability. To optimize its therapeutic efficacy, methods to increase its bioavailability—such as the use of quercetin glycosides or nanoparticle formulations—are being investigated [118]. Quercetin is a promising option for AD treatment because of its ability to regulate inflammation, oxidative stress, and other pathological processes. Nevertheless, more clinical research is necessary to confirm its effectiveness and determine optimal dosage regimens.

Neuroprotective mechanisms of functional foods. The diagram depicts how functional foods support brain health through four main mechanisms: antioxidant/metabolic support, anti-inflammatory effects, anti-amyloid/protein regulation, and cholinergic support [2, 10].

Abbreviations: ROS: Reactive oxygen species; Nrf2: Nuclear factor erythroid 2 related factor 2; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; Aβ: Amyloid-beta; AChE: Acetylcholinesterase; BuChE: Butyrylcholinesterase; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL-1β: Interleukin-1 beta.

5.12.2. Curcumin

The rhizome of Curcuma longa, or turmeric, contains a polyphenolic compound called curcumin, which has attracted significant interest due to its potential neuroprotective benefits in AD. It is a promising option in the treatment of AD due to its diverse mechanisms of action, which include anti-inflammatory, anti-amyloid, and antioxidant properties [116, 119].

Oxidative stress is one of the defining characteristics of AD, contributing to both neuronal damage and cognitive decline [109]. It has been demonstrated that curcumin activates the Nrf2 pathway, which results in the upregulation of HO-1, an enzyme essential for protecting cells from oxidative damage. This activation reduces oxidative stress-induced neuronal damage by boosting neurons' antioxidant capacity [120]. Along with its antioxidant effects, curcumin has strong anti-inflammatory properties. It prevents the transcription factor NF-κB, which controls the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, from becoming activated. By inhibiting NF-κB activation, curcumin lowers the synthesis of inflammatory mediators like ILs and TNF-α, which reduces the neuroinflammation linked to AD [121].

Curcumin also prevents Aβ peptides from pathologically aggregating. It has been shown to inhibit Aβ aggregation and encourage the disintegration of pre-existing fibrils, thereby lessening Aβ-induced neurotoxicity [122]. Further adding to curcumin's neuroprotective profile is its capacity to chelate metal ions, such as iron and copper, which are linked to oxidative stress and Aβ aggregation [123].

Curcumin's poor bioavailability is the main reason why clinical studies examining its effectiveness in AD have produced conflicting findings. However, developments in formulation techniques, such as the creation of phospholipid complexes and curcumin nanoparticles, have demonstrated promise in improving the drug's bioavailability and therapeutic effectiveness [124, 125]. Daily consumption of Theracurmin, a bioavailable curumin formulation, for 18 months considerably enhanced memory and attention in middle-aged and older adults with mild cognitive impairment, according to a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The Buschke Selective Reminding Test and Trail Making Test revealed cognitive improvements, while PET imaging revealed reduced Aβ and tau buildup in the amygdala and hypothalamus [126]. These effects are attributed to curcumin's anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-amyloid properties, which are further strengthened by nanoparticle technology's increased bioavailability [126, 127].

According to the study, long-term supplementation with bioavailable curcumin may slow cognitive decline in at-risk populations and provide neuroprotective benefits, despite its small sample size [126]. Although curcumin's direct brain penetration remains limited, these mood and cognitive benefits are likely mediated by its systemic actions, underscoring its potential as a low-cost, well-tolerated treatment to slow age-related cognitive decline [128].

5.12.3. Carotenoids

Carotenoids are vibrant pigments with significant antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that are present in fruits, vegetables, and seaweeds. Of all the known carotenoids, the most well-characterized and researched for their roles in various diseases and conditions are α-carotene, β-carotene, lutein, zeaxanthin, lycopene, and β-cryptoxanthin. When comparing AD patients to healthy controls, low blood carotenoid levels are commonplace, and plant-based diets are thought to be neuroprotective. Improved cognitive function is linked to increased levels of β-cryptoxanthin, an oxidized carotenoid, in the blood. Additionally, given that circulating α- and β-carotene levels are markedly lower in AD, there is evidence that they could function as non-invasive disease biomarkers [2].

An observational study found that adults with high serum levels of lutein and zeaxanthin or lycopene had a lower risk of AD mortality [129]. It has been demonstrated that these substances neutralize ROS, reducing oxidative damage to neural cells. By modifying inflammatory pathways, such as the inhibition of NF-κB activation, which is linked to the neuroinflammation associated with AD, carotenoids also demonstrate anti-inflammatory properties [130]. Carotenoids may also have neuroprotective effects by influencing other important pathways in AD, such as the regulation of tau phosphorylation and Aβ aggregation [131].

Therefore, including fruits and vegetables high in carotenoid content in the diet can offer a multimodal approach to managing AD, addressing inflammation and oxidative stress while also possibly slowing the course of the disease [130, 131].

5.12.4. Vitamins

Recent years have seen a thorough review of the role vitamins play in AD and cognitive disorders. They play a role in protecting the body against oxidative stress and damage. While vitamin E's role in AD pathogenesis and progression is the subject of much recent debate, deficiencies in vitamins A, D, K, and E are implicated in AD and its cognitive decline [2]. Emerging studies demonstrate how some vitamins may be able to control inflammation and oxidative stress in the development of AD. Due to its antioxidant qualities, vitamin E has been researched for its potential to shield neuronal membranes from oxidative damage [132].

High-dose vitamin E supplementation (2000 IU/day) has been shown in clinical trials, including the TEAM-AD study, to slow the functional decline of patients with mild-to-moderate AD. Despite a compelling case for vitamin E's effectiveness as an AD intervention, the available clinical data are still inconclusive [133, 134].

Additionally, vitamin D has been linked to cognitive function. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial investigated the effects of daily oral vitamin D3 supplementation (800 IU) over 12 months on cognitive function and Aβ-related biomarkers in older adults diagnosed with AD. The study involved 210 participants, who were randomly assigned to receive either vitamin D3 or a placebo. The results demonstrated significant improvements in cognitive performance. Additionally, plasma levels of Aβ42, APP, and BACE1 were significantly reduced in the intervention group compared to the placebo group. These findings suggest that vitamin D3 supplementation may positively influence cognitive function and modulate Aβ-related biomarkers in Alzheimer's patients. The authors concluded that larger-scale, longer-term randomized trials are necessary to further explore the potential therapeutic role of vitamin D in AD management [135, 136].

The metabolism of homocysteine depends on B vitamins, especially B6, B9 (folic acid), and B12. Elevated homocysteine levels are associated with a higher risk of AD [137]. According to the VITACOG trial, taking B vitamins significantly decreased the rate of brain atrophy in people with mild cognitive impairment, particularly in those with higher baseline homocysteine levels [138]. These results call for more research into the therapeutic potential of targeted vitamin interventions since they may have neuroprotective effects and interfere with the oxidative and inflammatory pathways implicated in AD.

5.12.5. Resveratrol

A polyphenol known as resveratrol is found in a variety of plants, including grapes, peanuts, cranberries, blueberries, and blackberries. It was shown in a study that grape powder containing resveratrol prevented changes in cerebral metabolism in people with mild cognitive impairment and was associated with enhanced working memory and attention; consequently, resveratrol is an antioxidant that may be useful in the treatment of AD [129]. According to preclinical research, resveratrol can lessen neuronal damage by reducing oxidative stress by activating the brain's antioxidant systems, including glutathione and superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) [139]. Furthermore, by preventing the synthesis of proinflammatory factors and reducing the activation of astrocytes and microglia, which are linked to AD pathology, resveratrol demonstrates anti-inflammatory properties [140].

The safety and effectiveness of resveratrol in AD patients have been investigated in clinical trials. According to a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, resveratrol is safe, well-tolerated, and may modify the course of some AD biomarkers [141]. Additionally, resveratrol supplementation preserved hippocampal volume and improved functional connectivity in people at risk for dementia, according to a proof-of-concept study [142]. Although more research is required to fully elucidate its clinical efficacy, these findings imply that resveratrol may offer therapeutic benefits in modulating oxidative stress and inflammation in AD.

5.12.6. Ebselen

Despite the fact that ebselen does not naturally occur in food, its selenium component can be acquired through selenium-rich foods. Brazil nuts—one of the best natural sources of selenium—as well as meats (such as beef and poultry), seafood (such as tuna and sardines), eggs, and whole grains are examples of functional foods high in selenium [143]. Numerous antioxidants, including ebselen, have been studied for their capacity to penetrate the BBB and function as neuroprotectants when given singly, in combination, or conjugated with other substances. The potential glutathione peroxidase-like effects of the selenium-containing compound ebselen, involved in the scavenging of free radicals, have also been evaluated. Selenium is a crucial trace element that, via oxidative stress resistance, keeps the brain's antioxidant activity intact [10]. Its free radical scavenging activity may be able to help treat AD. Using a combination of antioxidant compounds rather than just one may improve the drug therapy's overall antioxidant ability, increase the antioxidants' bioavailability in different cellular locations, and enhance their functionality [10, 129].

Furthermore, ebselen exhibits anti-inflammatory properties by regulating microglial activation and preventing the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which may lessen neuroinflammation linked to the advancement of AD [144]. According to preclinical research, ebselen can inhibit cerebral AChE activity, which may help maintain cholinergic neurotransmission, a process frequently impaired in AD [145, 146]. Although ebselen's effectiveness in treating conditions like stroke and bipolar disorder has been the main focus of clinical trials, its neuroprotective mechanisms present a promising avenue for research on AD [147].

5.12.7. Melatonin

A variety of functional foods serve as dietary sources of melatonin, with tomatoes, olives, barley, rice, and walnuts being among the most abundant sources [148]. Including these foods in the diet may help maintain endogenous melatonin levels, which may have neuroprotective effects and modulate oxido-inflammatory pathways linked to AD [149]. The pineal gland secretes the peptide hormone melatonin, which plays a role in controlling the circadian rhythm. It was discovered that the plasma and CSF of people with AD had decreased levels of melatonin at night [129]. Furthermore, the likelihood of early institutionalization is elevated in people with AD who have sleep disorders. Consequently, melatonin has garnered more attention as a potential treatment for AD because circadian rhythm disruptions might influence the development of oxidative stress in AD. Melatonin supplements may help regulate the circadian rhythm [129]. Melatonin's anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in microglial cell lines may indicate a key neuroprotective mechanism for the hormone's action against p-tau neurotoxicity [150]. Melatonin has been shown in preclinical research to have neuroprotective effects by lowering the synthesis of tau and Aβ [151]. In patients with mild to moderate AD, a randomized controlled trial showed that prolonged-release melatonin stabilized cognitive function and enhanced sleep quality over 6 months [152].

5.12.8. Silibinin

Silibinin, an antioxidant derived from Silybum marianum, is mostly present in milk thistle seeds and is not frequently found in everyday foods. On the other hand, silibinin can be found in herbal teas and milk thistle supplements. Furthermore, attempts have been made to include silibinin in functional foods; for instance, the creation of fermented milk products that contain silibinin seeks to improve its therapeutic potential and bioavailability [153, 154]. A study discovered that silibinin is a multi-target inhibitor of the enzyme AChE and Aβ peptide accumulation, pointing to a possible AD remedy [150]. Silibinin can reduce cognitive dysfunction and prevent Aβ aggregation, according to preclinical research [155]. Studies using APP/PS1 transgenic mice, for example, demonstrated that silibinin treatment altered the processing of amyloid precursor protein and decreased oxidative stress in the brain, improving cognitive function [156]. The strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of silibinin are thought to be responsible for its neuroprotective effects. It reduces oxidative damage by scavenging ROS and inhibits the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-1β, as well as the activation of microglia. These activities support the preservation of the oxido-inflammatory balance, which is essential for halting AD progression and neuronal damage [155, 157]. Despite limited clinical research on silibinin's effectiveness in AD patients, preclinical data suggest that it may be a neuroprotective agent. To completely clarify its therapeutic advantages and the best ways to deliver it, more clinical research is necessary.

5.12.9. Chlorogenic Acid

It has been demonstrated that chlorogenic acid, a phenolic acid extracted from fruits and vegetables, has neuroprotective properties in relation to AD [158, 159]. Its medicinal effect is mediated at the biochemical level by pro-inflammatory cytokine modulation and inhibition, as well as its effectiveness in scavenging free radicals, all of which aid in managing the course of neurological conditions [160]. In animal models of AD, preclinical studies have shown that chlorogenic acid is effective in lowering Aβ deposition, reducing neuroinflammation, and improving cognitive functions [161]. For example, an 8-week intervention that combined chlorogenic acid supplementation with aerobic exercise activated the Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) and Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1-Alpha (PGC-1α) signaling pathway, which reduced oxidative stress and improved cognitive performance in mice [162]. Additionally, chlorogenic acid has been shown to cross the BBB, allowing it to exert its neuroprotective effects directly within the central nervous system [163]. Although these results are encouraging, more clinical trials are required to fully elucidate chlorogenic acid's therapeutic potential and establish standardized dosing regimens for successful intervention in human populations [161, 164].

5.12.10. Mediterranean Diet

The potential benefits of the Mediterranean diet (MeDi), which is defined by a moderate intake of wine and fish and a high intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and olive oil, have been thoroughly investigated [165]. Its potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties are thought to support cognitive function and neuroprotection. Antioxidants such as vitamins C and E, carotenoids, and polyphenols, which are abundant in the MeDi, help scavenge free radicals and reduce oxidative damage in the brain [166]. Furthermore, anti-inflammatory components of the diet, including monounsaturated fats from olive oil and omega-3 fatty acids from fish, have been linked to decreased levels of inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP), collectively contributing to the diet’s neuroprotective effects [166, 167].