All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Metal-Tolerant Thermophiles: From the Analysis of Resistance Mechanisms to their Biotechnological Exploitation

Abstract

Extreme terrestrial and marine hot environments are excellent niches for specialized microorganisms belonging to the domains of Bacteria and Archaea; these microorganisms are considered extreme from an anthropocentric point of view because they are able to populate harsh habitats tolerating a variety of conditions, such as extreme temperature and/or pH, high metal concentration and/or salt; moreover, like all the microorganisms, they are also able to respond to sudden changes in the environmental conditions. Therefore, it is not surprising that they possess an extraordinary variety of dynamic and versatile mechanisms for facing different chemical and physical stresses. Such features have attracted scientists also considering an applicative point of view. In this review we will focus on the molecular mechanisms responsible for survival and adaptation of thermophiles to toxic metals, with particular emphasis on As(V), As(III), Cd(II), and on current biotechnologies for their detection, extraction and removal.

1. HEAVY METALS: TOXICITY AND TRANSFORMATION

Heavy metals are among the most persistent and toxic pollutants in the environment [1]. Even in small concentrations, they can threat human health as well as the environment because they are non-biodegradable. There is no widely agreed criterion for definition of a heavy metal. Depending on the context, this term can acquire different meanings: for example, in metallurgy a heavy metal may be defined by its density, in physics by its atomic number, and in chemistry by its chemical behavior [2]. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) does not consider these definitions correct; in this review, according to IUPAC, every “heavy” metal has the following characteristics: density exceeding 5.0 g/cm3; general behavior as cations; low solubility of their hydrates; aptitude to form complexes and affinity towards the sulfides.

In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that more than 25% of total diseases were linked to environmental factors including exposure to toxic chemicals [3]. For example, lead, [Pb(II)], one of the most common heavy metals, is thought to be responsible for 3% of cerebrovascular disease worldwide [4]; while cadmium, [Cd(II)], has been classified as carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) on the basis of several evidence in both humans and experimental animals [5, 6]. Furthermore, hazards associated with exposure to other metal ions like chromium [Cr(II)], mercury [Hg(I)], and arsenic [As(III) and As(V)], have been well established in the literature [7-12]. The risk related to heavy metal exposure depends on the concentration and time [13].

Table 1 reports the concentration limits of the most common heavy metals in drinkable water, suggested by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). It also shows the possible sources of these contaminants in drinking water and the potential health effects from long-term exposure [12, 14].

| Contaminant |

WHO (mg/L) |

EPA (mg/L) |

Potential Health Effects from Long-Term Exposure | Sources of Contaminant in Drinking Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | 0.010 | 0.010 | Skin damage or problems with circulatory systems, and may have increased risk of getting cancer | Erosion of natural deposits; runoff from orchards, runoff from glass and electronics production wastes |

| Ba | 7 | 2 | Increase in blood pressure | Discharge of drilling wastes; discharge from metal refineries; erosion of natural deposits |

| Cd | 0.003 | 0.005 | Kidney damage | Corrosion of galvanized pipes; erosion of natural deposits; discharge from metal refineries; runoff from waste batteries and paints |

| Cr (total) |

0.050 | 0.100 | Allergic dermatitis | Discharge from steel and pulp mills; erosion of natural deposits |

| Cu | 2 | 1.300 | Liver or kidney damage | Corrosion of household plumbing systems; erosion of natural deposits |

| Hg (inorganic) |

0.006 | 0.002 | Kidney damage | Erosion of natural deposits; discharge from refineries and factories; runoff from landfills and croplands |

| Pb | 0.010 | 0.015 | Kidney problems; high blood pressure | Corrosion of household plumbing systems |

| Sb | 0.020 | 0.006 | Increase in blood cholesterol; decrease in blood sugar | Discharge from petroleum refineries; fire retardants; ceramics; electronics; solder |

On the other hand, heavy metals naturally occur in the Earth’s crust. They are present in soils, rocks, sediments, air and waters and can be used and modified by local microbial communities, which are actively involved in metal geochemical cycles, affecting their speciation and mobility. Many metals are essential for life because they are actively involved in almost all aspects of metabolism: as examples, iron and copper are involved in the electron transport, manganese and zinc influence enzymatic regulations. However, their excess can disrupt natural biochemical processes and cause toxicity. For these reasons, all the microorganisms have evolved resistance systems to get rid of the cell of toxic metals as well as molecular mechanisms to maintain metal homeostasis. These systems frequently rely on a balance between uptake and efflux processes [15]. Because of microbial adaptation, microorganisms can also contribute to increase toxicity levels [16, 17]. For example, several studies in Bangladesh have demonstrated that microbial processes enhance the arsenic contamination in near- and sub-surface aquifers, because arsenate-respiring bacteria can liberate As(III) from sediments, adsorptive sites of aluminum oxides or ferrihydrite, or from minerals, such as scorodite [18].

Metal biotransformation impacts human health through the food chain: examples include the oxidation of Hg(0) to Hg(II), and the subsequent methylation to methylmercury compounds, which can be accumulated by fish and marine mammals in the aquatic environment [19].

Despite their relevant toxicity, in a report of the European Commission (named “Critical-Metals in the Path towards the Decarbonisation of the EU Energy Sector”), several heavy metals such as cadmium, chromium and lead are included into the classification of critical raw materials. According to the sustainable low-carbon economic policy of EU, these metals are expected to become a bottleneck in a near future to the supply- chain of various low- carbon energy technologies [20]. Therefore, it is very important to detect and recover these heavy metals to achieve both environmental safeguard and sustainable economic strategies. Common sources of heavy metals in this context include mining and industrial wastes, vehicle emissions, lead-acid batteries, fertilizers, paints, treated timber, aging water supply infrastructures, and microplastics floating in the world's oceans [21, 22].

2. METAL RESISTANCE MECHANISMS

Microorganisms able to tolerate high levels of heavy metal ions have evolved in ore deposits, hydrothermal vents, geothermal sites, as well as in different polluted sites [23]. Metal tolerance of thermophilic Bacteria/Archaea is due to several mechanisms, many also found in mesophilic counterparts, such as: extracellular barrier, metal ion transport into and outside the cell, the utilization of toxic metal ions in metabolism or the presence of metal resistance genes with different genomic localization (chromosome, plasmid or transposon) [24].

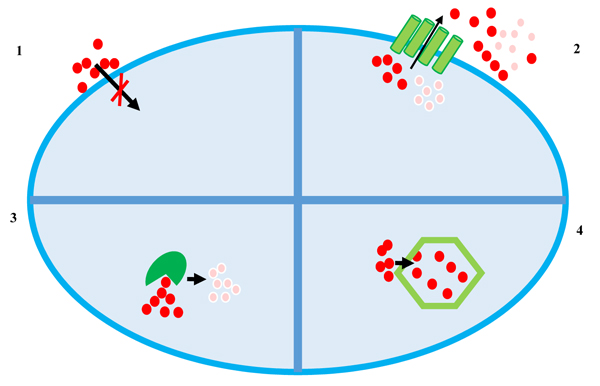

To date, at least four main mechanisms of heavy metal resistance, schematized in Fig. (1), are described which can be even found in the same microorganism [24-31]:

- Extracellular barrier;

- Active transport of metal ions (efflux);

- Enzymatic reduction of metal ions;

- Intracellular sequestration.

The cell wall or plasma membrane can prevent metal ions from entering the cell. Bacteria belonging to different taxonomical groups can adsorb metal ions by ionisable groups of the cell wall (carboxyl, amino, phosphate and hydroxyl groups) [32]. However, many metal ions enter the cell via the systems responsible for the uptake of essential elements: for example, Cr(II) is transported inside the cell via sulphate transport system [33], whereas Cd(II), Zn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Mn(II), enter the cells using systems of magnesium transport [34]. Moreover, As(V) is taken into cells by phosphate transport systems and As(III) has been shown to be taken up by glucose permeases [35].

Both in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria the arsenic resistance system is composed by operons of 3-5 genes carried on plasmids or chromosomes; the two most common contain either five genes (arsRDABC), as in the plasmid R773 of the Escherichia coli, or three genes (arsRBC), as in the plasmid pI258 of Staphylococcus aureus [36, 37]. The arsR gene encodes a trans-acting repressor of the ArsR/SmtB family involved in transcriptional regulation [30], arsB encodes an As(III) efflux transporter [38], and arsC encodes a cytoplasmic arsenate reductase that converts As(V) to As(III), which is extruded outside the cell [39]. Where present, ArsD is a metallochaperone that transfers trivalent metalloids to ArsA, the arsenite-stimulated efflux ATPase [31].

2.1. Transport of Metal Ions: Efflux Systems

The majority of thermophilic microorganisms (both belonging to Archaea and Bacteria domains) are resistant to heavy metals thanks to an active transport and/or efflux of metal ions outside the cells. The genetic determinants of efflux systems can be localized on chromosomes [40] and on plasmids [41]. In most cases, the expression of metal efflux genes is transcriptionally controlled by co-transcribed metal sensor proteins [42].

In microorganisms, efflux systems consist of proteins belonging to three families: CDF (cation diffusion facilitator), P-type ATPases and RND (resistance, nodulation, cell division) [43]. CDF proteins and P-type ATPases of Gram-negative bacteria transport specific substrates through the plasma membrane into the periplasm. CDF proteins are metal transporters occurring in all the three domains of life whose primary substrates are mainly ions of divalent metals like Zn(II), Co(II), Ni(II), Cd(II), and Fe(II) and export metals through a chemiosmotic gradient formed by H+ or K+ [44, 45]. Most of these proteins have six transmembrane helices containing a zinc-binding site within the transmembrane domains, and a binuclear zinc-sensing and binding site in the cytoplasmic C-terminal region [46]. These proteins exhibit an unusual degree of sequence divergence and size variation (300-750 residues).

Differently from CDF-proteins, P-type ATPases transfer both monovalent or bivalent metal ions with high affinity for sulfhydryl groups (Cu(I)/Ag(I), Zn(II)/Cd(II)/Pb(II)) and use ATP hydrolysis to transport ions across cellular membranes [43]. They are composed of three conserved domains: i) a transmembrane helix bundle, allowing substrate translocation; 2) a soluble ATP binding domain containing a transiently phosphorylated aspartate residue; 3) a soluble actuator domain (AD). Those belonging to P1B-type are capable to drive the efflux out of cells of both essential transition metal ions (e.g., Zn(II), Cu(I), and Co(II)) and toxic metals (e.g., Ag(I), Cd(II), Pb(II)) contributing to their homeostasis maintenance. In a recent study on a huge number of P1B-type ATPase they have been classified into seven distinct subfamilies (1B-1 1B-7) but the molecular basis of metal ion specificity remains unclear [47]. Several thermophilic P1B-type ATPases involved in metal efflux have been characterized. The thermophilic bacterium Thermus thermophilus HB27 contains in its genome three genes coding for putative PIB-type ATPases: TTC1358, TTC1371, and TTC0354; these genes are annotated, respectively, as two putative copper transporter (CopA and CopB) and a zinc-cadmium transporter (Zn(II)/Cd(II)-ATPase) [48], involved in heavy metal resistance. Archaeoglobus fulgidus possesses a CopA protein driving the outward movement of Cu(I) or Ag(I) characterised by a conserved CPC metal binding site and a cytoplasmic metal binding sequence (also containing cysteine residues) at its N- and C- terminus [49].

Members of the RND family are efflux pumps, especially identified in Gram-negative bacteria that can be divided in subfamilies depending on the substrate transported; they actively export heavy metals, hydrophobic compounds, nodulation factors [50]. The heavy metal efflux (HME) RND sub-family functions for metal ion efflux powered by a proton-substrate antiport. The prototype family member from E. coli is CusA; it works in conjunction with the membrane fusion protein CusB and the outer-membrane channel CusC forming a tripartite complex spanning the entire cell envelope to export Cu(I) and Ag(I) [51]. The crystal structures of CusA in the absence and presence of bound Cu(I) or Ag(I) has been recently solved providing structural information [52].

To the best of our knowledge, thermophilic microbial genomes do not contain genes encoding proteins of the HME-RND family. A Blast analysis of CusA against thermophilic genomes revealed homology with integral membrane proteins of the ACR (Activity Regulated Cytoskeleton Associated Protein) family involved in drug and/or heavy metal resistance [53].

2.2. Enzymatic Reduction of Metal Ions: Metal Reductases

Many thermophilic microorganisms employ intracellular enzymatic conversions combined with efflux systems to obtain heavy metal resistance. Enzymatic reduction of metal ions can result in the formation of less toxic forms like Hg(II) reduced to Hg(0), Cr(V) converted into Cr(III) [23] or, as in the case of As(V), reduction in the more toxic As(III) which is the only form extruded by the cell.

Several thermophilic metal reductases have been described so far; for example, TtArsC from Thermus thermophilus HB27 is an arsenate reductase which enzymatically converts As(V) in As(III) [54] using electrons provided from the thioredoxin-thioredoxin reductase system and employing a catalytic mechanism in which the thiol group of a N-terminal cystein performs a nucleophilic attack on the arsenate [54]. As told before the arsenite is then extruded by a dedicated efflux protein.

MerA from Sulfolobus solfataricus is flavoprotein that catalyzes the reduction of Hg(II) to volatile Hg(0), converting toxic mercury ions into relatively inert elemental mercury [55].

The thermophilic bacteria isolated from various ecological niches can also reduce a broad spectrum of other heavy metal ions such as Cr(V), Mo(VI) and V(V) [56] that serve as terminal acceptors of electrons during their anaerobic respiration [57].

These systems are generally finely regulated by specific transcription factors. As an example, the transcription of the arsenic resistance system of T. thermophilus HB27 is regulated by TtSmtB, a protein belonging to the ArsR/SmtB family which acts as the As(V) and As(III) intracellular sensor [30]. In the absence of metal ions, the protein binds to regulatory regions upstream of TTC1502, encoding TtArsC, and TTC0354, encoding the efflux membrane protein TtArsX, (a P1B- type ATPase, see above). In a recent study from our group it was demonstrated that TtArsX and TtSmtB are also responsible for Cd(II) tolerance [58].

2.3. Metal Intracellular Sequestration

Another common mechanism to inactivate toxic metal ions is the intracellular sequestration or the complexation of metal ions by various compounds in the cytoplasm. The metallothioneins and phytochelatins are two classes of peptides rich in cysteine residues which bind metal ions through the sulfhydrylic groups [59].

Metallothioneins constitute a superfamily of ubiquitous cytosolic small (25–82 amino acids), cysteine-rich (7–21 conserved Cys residues) proteins able to bind metal ions, mainly Cd(II), Zn(II) and Cu(I), via metal-thiolate clusters in the absence of aromatic amino acids and histidine residues [60]. They are multifunctional proteins whose synthesis is stimulated by heavy metals and other environmental stressors; based on this latter evidence the metallothionein promoter of Tetrahymena thermophila has been employed in the development of a whole-cell biosensor for the detection of heavy metals [61].

Among prokaryotes, the ability to synthesize metallothionein has been demonstrated in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 which contains two genes smtA and smtB inducible by Cd(II) and Zn(II). The peptide contained fewer cysteine residues than the eukaryotic metallothionein [62].

3. APPLICATIONS IN BIOTECHNOLOGY

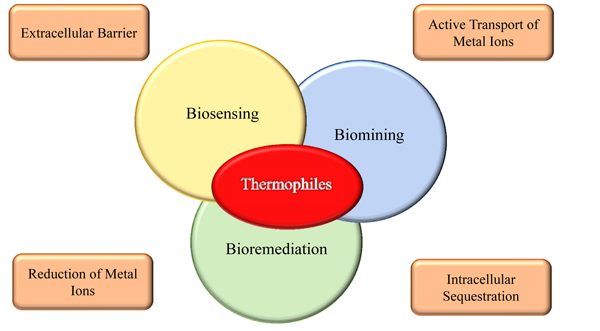

A detailed understanding of the molecular mechanisms responsible for resistance to toxic metals in metal-tolerant microorganisms is also crucial for a potential use in the environmental monitoring of metal contamination and to set up bioremediation processes, the most promising being biosorption and removal as insoluble complexes Fig. (2).

The traditional approach for monitoring the environmental pollution is based on chemical or physical analysis and allows highly accurate and sensitive determination of the exact composition of any sample. These analyses require specialized and expensive instrumentations, as the ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma - Mass Spectrometry) which, to date, is the most adopted technique for detecting heavy metals [63].

The need for accurate, not expensive, on-site and real-time measurements has led to the development of sensors based on biomolecules and nanomaterials [63-66]. Biosensors are analytical devices which integrate a biological recognition element with a physical transducer to generate a measurable signal proportional to the concentration of the analyte [67-69]. The use of biological molecules is a considerable advantage in the sensor field, because of their high specificity: these sensors are based on the specific interaction between enzymes and their substrates, antibodies and antigens, target molecules to their receptors, or the high affinity of nucleic acid strands to their complementary sequences [67]. Nevertheless, some biomolecules can be too labile for the exploitation on the marketplace. In this context, the biomolecules of the thermophiles are more stable at high temperatures than the mesophilic counterparts. In fact they have already been exploited in biotechnology, as demonstrated by the development of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and the use of thermozymes in many industrial applications [70-73].

The recent developments in nanotechnology have also opened new horizons for biosensing: nanomaterials are attractive because of their unique electrical, chemical and physical properties (i.e. size, composition, conductivity, magnetism, mechanical strength, and light-absorbing and emitting). The most studied of them, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, metal nanoparticles (MNPs), and quantum dots (QDs), have been especially targeted for developing novel biosensors [64, 73-76]. An example of a successful match between thermophilic biomolecules and nanomaterial for the development of a heavy metal biosensor is reported by Politi et al. [77, 78]. In this work, TtArsC, the arsenate reductase from T. thermophilus HB27 [54] was conjugated to polyethylene glycol-stabilized gold nanospheres. The new nanobiosensor revealed high sensitivities and limits of detection equal to 10 ± 3 M-12 and 7.7 ± 0.3 M-12 for As(III) and As(V), respectively [77, 78].

A detailed understanding of the molecular mechanisms responsible for resistance to toxic metals is crucial to develop whole cell biosensors for the detection of chemicals in the environment so that not only thermophilic biomolecules, but also thermophilic microorganisms can constitute heavy metal biosensors. Many whole-cell biosensors for metal ions detection have been already described in the literature based on the realization of reporter systems containing regulatory cis-acting sequences interacting with the cognate transcriptional metal sensor repressor; however, to date, there are few reports on thermophilic whole cell biosensors [79, 80].

In the work by Poli et al. [57], Anoxybacillus amylolyticus, an acidothermophilic bacterium isolated from geothermal soil samples in Antarctica, was observed to be resistant to metals like Ni(II), Zn(II), Co(II), Hg(II), Mn(II), Cr(VI), Cu(II) and Fe(III). A decrease in α-amylase activity, correlated with a decrease in α-amylase production, was observed in the presence of heavy metals: it is speculated to use it as a toxicological indicator of heavy metals in a potential microbial bioassay employing whole cells [57].

Biomining and bioremediation represent a new branch of biotechnology, named biometallurgy, addressed at heavy metal recovery including the processes that involve interactions between microorganisms and metals or metal-bearing minerals [81]. Biomining refers to the exploitation of microorganisms to extract and recover metals from ores and waste concentrates (the term is often used synonymously with bioleaching when the metals are solubilized during the process); on the other hand, bioremediation focuses on the transformation of a toxic substance into a harmless or less toxic one from contaminated sites [82, 83]. In this contest, among the heavy metals resistance systems developed by microorganisms, and in particular by thermophiles, biosorption and bioaccumulation are emerging as promising low-cost methodologies for bioremediation [84, 85]. Biosorption and bioaccumulation are two processes that consist into the ability of microorganisms to accumulate heavy metals from wastewater through metabolic pathways or physical-chemical uptake; but while biosorption is a passive process depending on the composition of the cellular surface and following a kinetic equilibrium, bioaccumulation is an energy driven process and requires an active metabolism [59].

Several examples of biosorption and bioaccumulation are provided by microorganisms belonging to Geobacillus sp., which are highly tolerant to Cd(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) [86-88]. Özdemir, S. et al, indicated a G. toebii subsp. decanicus as an efficient viable biosorbent for heavy metals. This study clearly shows that thermophiles can be used for removal and recovery of heavy metals from industrial wastewater [89].

The interest into the potential applications of heavy metal resistant thermophiles has led to the development of tools and assays for screening them on lab scale [61, 90-92], with the final goal to design and set up bacterial bioprocesses on the industrial scale [93-95]. Table 2 summarizes some examples of bioprocesses employing heavy metals performed by thermophiles.

| Heavy Metals | Microrganisms | Bio Processes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CuFeS2 |

Leptospirillum ferriphilum Acidithiobacillus caldus |

Bioleaching | Zhou H.B. et al, 2009 [94] |

| Fe(II) | Sulfobacillus sp. | Bioleaching | Hawkes R. et al, 2006 [92] |

| As(III), As(V) | Thermus thermophilus | Biosensing | Politi J. et al, 2015 [77] |

| Ni(II), Zn(II), Co(II), Hg(II), Mn(II), Cr(VI), Cu(II) and Fe(III) | Anoxybacillus amylolyticus | Biosensing | Poli et al, 2008 [57] |

| Cd(II) | Tetrahymena thermophila | Biosensing | Amaro F. et al, 2011 [61] |

| Cd(II), Cu(II), Ni(II), Mn(II), Zn(II) |

Geobacillus toebii subsp. decanicus Geobacillus thermoleovorans subsp. stromboliensis |

Biosorption | Özdemir, S. et al, 2012 [86] |

| Cd(II) |

Geobacillus stearothermophilus Geobacillus thermocatenulatus |

Biosorption | Hetzer, A. et al, 2006 [87] |

| Fe(III), Cr(III), Cd(II), Pb(II), Cu(II), Co(II), Zn(II), Ag(I) | Geobacillus thermodenitrificans | Biosorption | Chattereji S.K. et al, 2010 [88] |

4. RESULT

Metal-tolerant thermophiles exhibit metabolic and physiological features that distinguish them from other major life groups due to their adaptation to extreme environments.

CONCLUSION

Most of the knowledge regarding mechanisms of adaptation/resistance to toxic metals has been discovered using traditional microbiological/biochemical techniques and thanks to the use of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics as well as to the recent development of genetic tools for many of these organisms. With the advent of next-generation sequencing technologies, comparative genomics and metagenomics projects, it appears that even novel metabolic features can be discovered, further expanding our understanding of environmental microbiology. Such an integrated view opens to new opportunities for biotechnological applications in commercially relevant processes such as the monitoring of metal concentrations in the environment, the recovery of precious and strategic metals and the setup of microbial-based remediation strategies.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II that financed the original research project: “Immobilization of Enzymes on hydrophobin-functionalized Nanomaterials”.