All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Alzheimer’s Disease and Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) Gene Polymorphisms

Abstract

Background:

Some studies have indicated that human paraoxonase 1 (PON1) activity shows a polymorphic distribution. The aim of this study was to determine the distribution of PON1 polymorphism in patients with Alzheimer’s disease in Gorgan and compare it with a healthy control group.

Method:

The study included 100 healthy individuals and 50 patients. Enzyme activity and genetic polymorphism of PON1 were determined.

Result:

There were significant differences in distribution of genotypes and alleles among patients and control group. The most common genotype was CT in patients and control group, while the most frequent alleles were T and C in patients and controls, respectively. There was a statistically significant variation between serum PON1 activity and –108C> T polymorphism. The highest PON1 enzyme activities in the patients and controls were found in CC, while lower enzyme activities were seen in CT and TT genotypes in both genders and age groups.

Conclusion:

Onset of Alzheimer’s disease may depend on different polymorphisms of the PON1 enzyme. Late or early-onset of Alzheimer’s disease may also depend on age and gender distribution, especially for arylesterase enzyme. Further studies on polymorphism of the enzyme are necessary for interpretation of possible polymorphic effects of enzyme on PON1 activity in humans.

1. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia [1]. It affects one in eight individuals aged over 60 years [2]. The prevalence of dementia is increasing and is expected to reach 24 million by the year 2040 [3, 4]. The increasing prevalence of AD has been reported in some countries [5]. A study has shown an association between paraoxonase 1 (PON1) activity and the pathogenesis of AD [6]. Human PON1 exhibits both paraoxonase and arylesterase activities. It hydrolyzes organophosphate compounds such as paraoxon, and aromatic carboxylic acid esters [7-10]. PON1 is associated with high-density lipoprotein (HDL) [11]. The enzyme reduces accumulation of the lipid peroxides in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) [12]. PON1 is a main anti-atherosclerotic component of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) [13, 14]. PON1 also protects against bacterial infection by destroying the bacterial signalling molecules [15]. The PON1 polymorphism is associated as risk factor for neurological diseases [16-18]. Several studies have shown that PON1 status and oxidative stress could play important roles in many neurodegenerative diseases [16, 19-25]. More than 160 polymorphisms have been shown in the PON1gene [26]. Study of Primo-Parmo et al. revealed that PON1 included three genes: PON2, PON3 and PON1 that are located on the long arm of human chromosome 7 (q21.22) [27]. The expression of PON gene family members occurs in different types of tissues in the human body [27]. The PON3 and PON1 genes, and PON2 gene are expressed and synthesized in the liver and various tissues (brain, liver, kidney, and testis), respectively [28]. Secreted PON1 and PON3 enzymes from liver cells are found in the blood circulation bound to high-density lipoproteins, while PON1 activity predominates in human serum [29]. The PON2 enzyme synthesized in many tissues is not released from the cells [21]. The PON1 is the best investigated and described member of the family [30]. Several polymorphisms of PON1 gene have been reported. These polymorphisms may be associated with PON1 expression and enzyme activity [31-38].

Different distribution of PON1 gene polymorphism makes these polymorphisms important in different ethnic groups. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine the distribution of PON1 polymorphism in patients with AD and compare it with a control group.

2. MATERIALS AND METHOD

2.1. Study Subjects and Sample Collection

The study included 100 healthy unrelated individuals (63 men and 37 women) and 50 Alzheimer’s patients with late-onset form of the disease (31 men and 19 women). The mean age of Alzheimer’s patients and control group was 75.01± 69.09 and 74.06± 66.10 years, respectively. The patients were directed to an elderly nursing home in Gorgan, Iran. Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, liver disease, renal failure and chronic infectious disease were excluded. The control group was selected from the close relatives of Alzheimer’s patients. Both groups were matched in terms of age and gender. The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of Deputy of Research at Golestan University of Medical Sciences. Alzheimer’s patients were diagnosed by a neurologist using MMSE (Mini Mental State Examination) [32]. Written consent was obtained from close relatives of all subjects. Ten ml blood samples were collected in EDTA-tubes and serum tubes for determination of PON1 genotypes and PON1 activity, respectively. Collected samples were stored at −20°C until analysis.

2.2. Determination of PON1

Determination of serum paraoxonase and arylesterase activities were carried out by Brophy et al. method [33] using spectrophotometry technique (Model JENWAY 6105 UV/VIS) at the Metabolic Disorders Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences.

2.3. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism Analysis (PCR-RFLP)

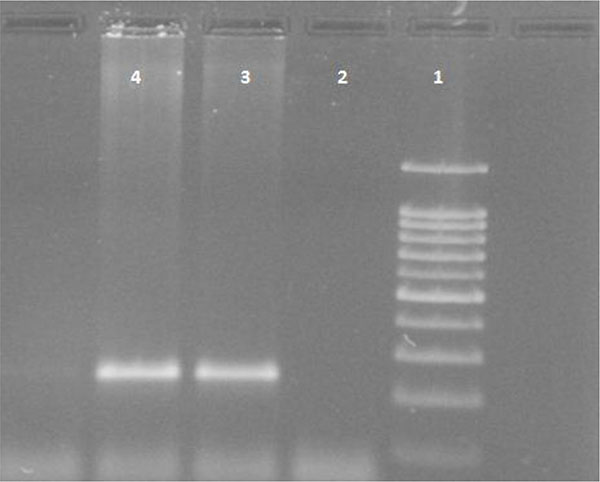

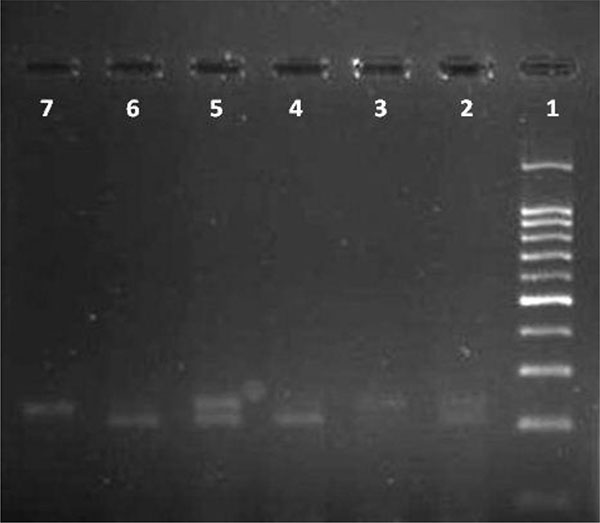

White blood cells were used for DNA extraction by salting-out method [34]. Extracted DNA was dissolved by sterilized distilled water. The PCR and PCR-RFLP techniques were used to determine the polymorphism of -108C>T using Genetix CG palm-thermocycler (India). Amplification was performed for DNA fragment containing polymorphic site –108C>T. A 25 μl reaction mixture was prepared for the PCR process including buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl, pH = 8.4 and 500 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2) (Fermentas), 0.3 mM deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate (dNTP), 0.4 U/μl Taq polymerase (Fermentas), 0.3 μM of each primer (Bioneer), 20 ng genomic DNA and 11.1 μL sterile distillated water. Digestion of PCR products (32μl) was performed by restriction enzymes, BsrBI (Fermentas) at 37oC for 16 hours. The PCR amplification conditions included initial denaturation (35 cycles at 95oC for 3 minutes), denaturation (at 94oC for 30 seconds), annealing (at 68oC for 30 seconds), extension (at 72C for 60 seconds) and final extension (at 72oC for 7 minutes). Figs. (1 and 2) show the PCR products before and after digestion with the restriction enzyme (BsrBI), respectively. Agarose gel (2%) stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) was used for electrophoresis of DNA fragments (Apelex, France). The bands were detected using a Polaroid Gel Camera. In Fig. (1), undigested fragment (240 bp) was detected. In Fig. (2), digested fragment (212 bp) was detected for C-108 genotypes CC, CT and TT. Detection of mutations was performed using the following primers:

Forward primer: 5' AGCTAGCTGCCGACCCGGCGGGGAGGAG 3'

Reverse primer: 5' GGCTGCAGCCCTCACCACAACCC 3'.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

SPSS software version 16 was used for data analysis (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Chi-square test was used to compare allele and genotype frequencies. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the distribution for PON1 activity. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare PON1 activity and genotype. Comparisons of PON1 activity with genotype distribution of Alzheimer’s patients and control group were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney test. P-value of less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

This study revealed the PON1 activity and the genotype and allele frequencies for 108C>T polymorphism of this gene in Alzheimer’s patients and healthy controls. The frequencies of PON1 genotypes and alleles are shown in Table (1). There were significant differences in distribution of –108C>T genotypes and alleles among Alzheimer’s patients and the control group (P = 0.03). The most common genotype was CT in the patients (54%) and controls (60%), while polymorphism frequencies of both CC and TT genotypes were lower. The most frequent alleles were T (59%) and C (55%) in Alzheimer’s patients and controls, respectively. Table (2) shows the association between PON1 enzyme activity and promoter region polymorphism in both groups. Table (2) indicates that there is statistically significant variation between serum PON1 activity and –108C>T polymorphism. Tables (3 and 4) show the PON1 enzyme activity in association with promoter region polymorphism in Alzheimer’s patients, in terms of gender and age. The highest PON1 enzyme activity was found for CC in the patients and controls, while lower enzyme activities were observed for CT and TT genotypes in both genders and age groups.

| Polymorphism | Genotype N=150 |

Frequency | Allele N=300 |

Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| -108C>T (Alzheimer patients) |

CC CT TT |

7 27 16 |

14 54 32 |

C T |

41 59 |

41 59 |

| 108C>T (Control) |

CC CT TT |

25 60 15 |

25 60 15 |

C T |

110 90 |

55 45 |

| P value | 0.03 | |||||

| Enzymes Activity (IU/A) |

Genotypes (Alzheimer patients) |

Genotypes (control) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC CT TT | CC CT TT | |||||

| Paraoxonase | 45.42* | 27.20* | 13.9*1 | 76.44 | 43.07 | 37.0 |

| Arylesterase | 41.0* | 25.81* | 18.06* | 77.56 | 44.45 | 29.66 |

(IU/L= 1 international unit of enzyme activity is explained as enzyme catalyzes the reaction.

rate of 1 μmol per minute in an assay system).

| Genotype | n | Mean Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paraoxonase Activity (IU/L) |

Arylesterase Activity (IU/L) |

||

|

Men(n=31) CC CT TT P value |

22 50 23 |

72.32 43.59 34.33 < 0.001 |

74.50 44.55 30.15 < 0.001 |

|

Women (n=19) CC CT TT P value |

10 37 8 |

37.70 28.66 12.81 0.009 |

38.35 27.96 12.25 0.004 |

| Genotype | n | Mean Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paraoxonase IU/L Activity |

Arylesterase U/L Activity |

||

|

≤70 (n=31) CC CT TT P value |

28 52 12 |

66.79 40.09 26.96 < 0.001 |

67.68 39.92 25.58 < 0.001 |

|

>70 (n=19) CC CT TT P value |

4 35 19 |

39.00 32.80 21.42 0.01 |

43.00 32.80 21.42 0.3 |

4. DISCUSSION

Some studies have indicated that human PON1 activity showed a polymorphic distribution. This polymorphism could be identified subjects with different paraoxonase 1 activity [26]. Gene frequencies may vary among different ethnic groups [39]. It is shown that PON1 activity may change up to 40-fold in some population [26, 39, 40]. Thus, it is important to determine the association between genetic polymorphism and status of the PON1 gene in Alzheimer’s patients. Our study showed the activity, genotype and allele frequencies for 108C>T polymorphism in healthy controls and Alzheimer’s patients. The present study confirms that PON1 activity is significantly lower in Alzheimer’s patients compared to controls. Low arylesterase activity may be a predictive risk factor for this disease. Pola et al. [41] and also Shi et al. [42] in a different study on Chinese population did not find any difference in enzyme activity of Alzheimer’s patients and controls. Helbecque et al. [43] and Cellini et al. [44] emphasized the importance of promoter -108C>T polymorphism, which may be a risk factor for AD. It was shown that there is an association between the PON1 gene promoter polymorphism and PON1 activity [45]. Although it is not clear how the mechanism of PON1 affects risk of AD, studies have revealed an association between low PON1 activity, elevated oxidative stress, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and dementia [46-49]. Many studies have revealed the association between PON1 polymorphism and AD [44, 50-56], while some studies have found no association between PON1 polymorphism and AD in African Americans or Caucasians [50]. The results of the present study showed a significant association between PON1 polymorphism and risk of AD, which is in agreement with other studies [44, 50-56]. Inconsistent with our findings, research on patients with AD has shown that there is no association between PON1 polymorphism and the development of the disease [57, 58]. PON1 may have a protective role in patients with AD [59]. Studies on other neurodegenerative diseases (Multiple sclerosis and Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) have revealed no association between PON1 polymorphism or activity and these diseases. Findings of some studies have indicated that PON1 may play an important role in the pathogenesis of neurological disorders [59, 60]. In the present study, PON1 polymorphism significantly affected PON1 activity. PON1 activity was the highest in CC and the lowest in TT genotype of promoter -108C>T polymorphism. Our results were in accordance with other findings [35, 61]. In this study, the -108 polymorphism revealed a significant difference in Alzheimer’s patients compared to controls (T allele was more frequent). Some studies have shown that -108 region is the only position that does not differ in allele frequency, between white and Japanese populations. This indicates that this polymorphism may show no specific differences in allele frequencies across different ethnic groups [35], which is not in agreement with our study. Some other findings suggested that the -108 polymorphism shows the greatest effect on arylesterase activity. This polymorphism may be associated with activity variance that is independent from the -108C site [35]. There is a relationship between the -108C allele and the PON1 genotype and disease. The -108 regulatory-region polymorphism has an important effect on PON1 expression in humans [35]. Our study showed a significant association between PON1 polymorphism and PON1 activity among different gender and age groups. The highest enzyme activity was observed in the CC genotype. Alzheimer’s patients older than 70 years have lower enzymatic activity (arylesterase and paraoxonase activities) than patients under 70 years old (except for arylesterase enzyme activity for age above 70 years old). This means that the disease may not begin late in life. Our study also showed that the PON1 activity in different genotypes of enzyme was lower in women than in men with AD. This means that women may be more susceptible to this disease compare to men. PON1 promoter polymorphism may affect PON1 expression. The association of the CC genotype with high PON1 activity has been reported to be stronger than the TT genotype [38], which is in agreement with our study. Our findings confirmed that the PON1 gene polymorphism affect serum PON1 activity. This may indicate a possible association between PON1 gene polymorphism with the progression of AD in the study subjects. Some studies suggested that PON1 does not cross the blood-brain barrier. Paraoxonase may express in brain or enter pathways that can disturb the brain [62]. Limited sample size is one of the limitations of the present study, because of small number of eligible Alzheimer’s patients in the elderly nursing home for this study. Our study subjects had not fasted before sample collection and the patients were not under any therapeutic regimen.

CONCLUSION

Onset of AD may depend on different polymorphism of enzymes, age and gender distribution. Further studies on polymorphism of enzymes are necessary for interpretation of possible polymorphic effects of enzyme on PON1 activity in humans.

FUNDING

This work has been supported by the Research Deputy of Golestan University of Medical Science.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals/Humans were used for studies that are base of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Research Deputy of Golestan University of Medical Sciences for financial support. This research project was derived from MSc thesis in Clinical Biochemistry. The corresponding author wishes to thank Miss Raheleh Shakeri for her sincere help.

REFERENCES

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]

[PubMed Link]